Cardinal Pietro Gasparri (1852–1934), Rome(?); Enrico Marinucci, Rome, 1934; Alessandro Contini Bonacossi (1878–1955), Rome and Florence, 1935(?); M. Knoedler and Co., New York;1 Hannah D. and Louis M. (1887–1957) Rabinowitz, Sands Point, Long Island, N.Y.

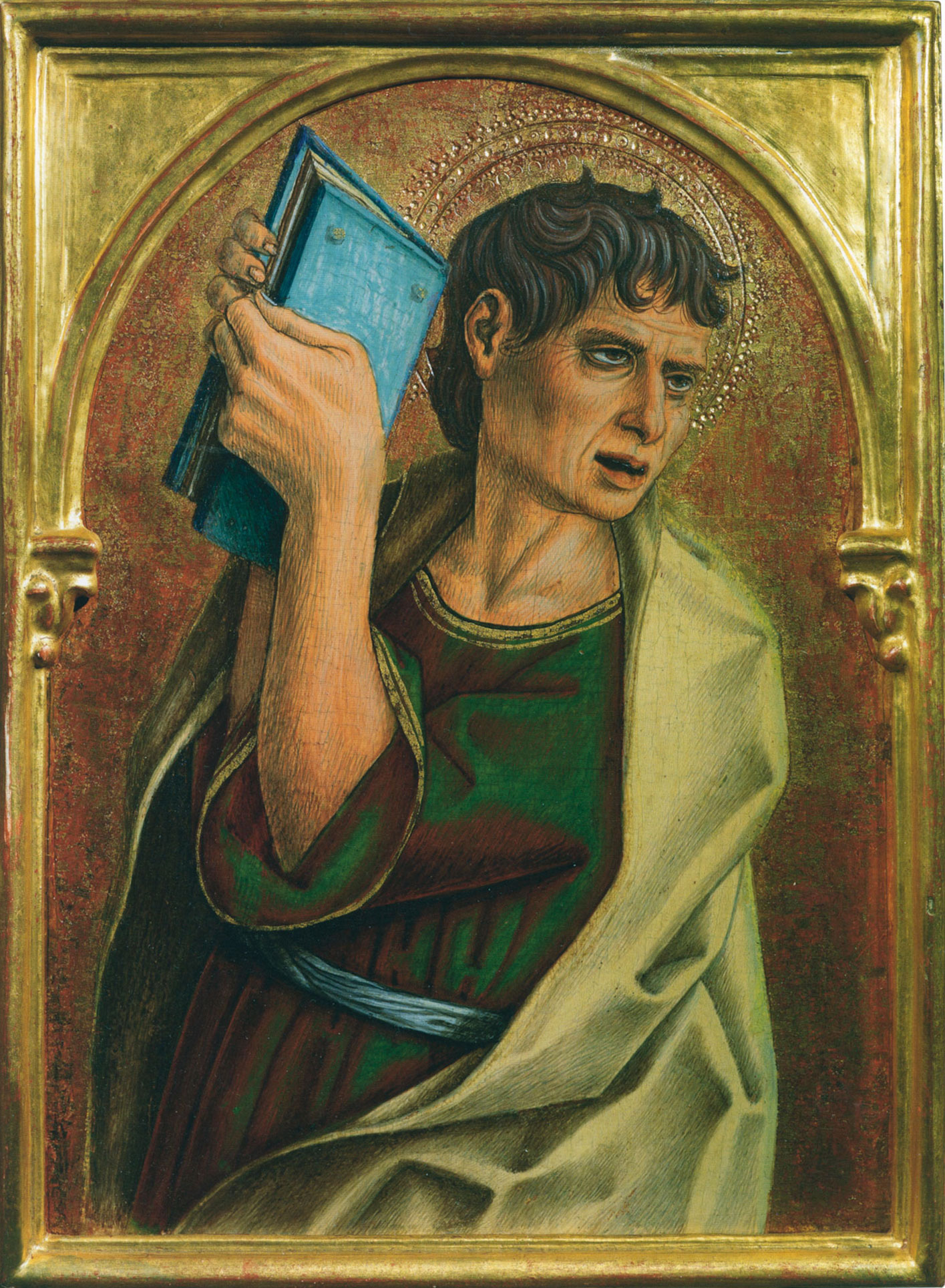

The panel, of a horizontal grain with a pronounced convex warp, is 2 centimeters thick and has been neither thinned nor cradled. Eight forged nails, not original to the panel or its framing, have been driven into the right edge of the panel. An engraved line defines the edge of the picture field at all sides, including the forms of missing capitals supporting the arched top of the frame. The panel has been cut on the right to just inside the scribed line below the capital and on the left 1 centimeter outside the scribed line. Gesso preparation at this side and in the spandrels above the arch has been partially scraped away, but it is intact below the scribed line to the bottom edge of the panel, which appears to be original. The gold background is abraded and two large losses—one to the left of Saint Peter’s shoulder and the other to the right of his forehead—have been left as exposed bolus and toned gesso. The paint surface has been lightly abraded overall but is largely intact and generally well preserved. Minor flaking losses in the silver keys and across the knuckles of the saint’s right hand have been retouched. A larger loss in the lower-right corner has been left as exposed gesso.

The Yale Saint Peter is part of a group of seven predella fragments by Carlo Crivelli that have been universally recognized as elements of a single complex. The six other components, comparable in dimensions, format, and style, and with identical tooling in the haloes, comprise a Blessing Redeemer formerly in the Kress collection and now in the El Paso Museum of Art (29.8 × 26.2 cm) (fig. 1); a Saint Bartholomew (fig. 2) and Saint John the Evangelist (fig. 3) in the Museo d’Arte Antica at the Castello Sforzesco, Milan (28 × 19.5 cm each); a Saint Andrew formerly in the Proehl collection, Amsterdam (27.5 × 19.5 cm) (fig. 4);2 a Saint James Major in the Andreas Pittas collection, London (27.7 × 21 cm) (fig. 5); and an unidentified Apostle Saint formerly in the Alana Collection, Newark, Delaware (28 × 20.7 cm) (fig. 6).3 It is generally assumed that the El Paso Redeemer stood at the center of the predella, with the Yale Saint Peter to its left and the other apostles lined up alongside them, following the formula of Carlo Crivelli’s signed and dated 1473 polyptych for the cathedral of Sant’Emidio in Ascoli Piceno (fig. 7) and the later altarpiece executed by the artist with his brother, Vittore, for the church of San Martino in Monte San Martino (Macerata).4 It is likely that the dismembered predella, like that of the Sant’Emidio Polyptych, included at least ten of the twelve apostles and that other panels in the series are yet to be identified.

The Yale Saint Peter and the El Paso Blessing Redeemer were first published by William Suida in 1934, when they were both in the collection of Enrico Marinucci in Rome.5 Not much is known of Marinucci, although a 1936 letter from Enrico Cappiello, an agent for Marinucci, to the then director of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (now the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) in Kansas City, Missouri, indicates that Marinucci had inherited at least some of the pictures in his collection from his uncle Cardinal Pietro Gasparri, who had died in 1934.6 A Marchigian native, Gasparri had been Secretary of State to Popes Benedict XV and Pius XI and was among the most powerful members of the Vatican hierarchy.7 Although it cannot be definitely ascertained whether the Yale and El Paso panels once belonged to the cardinal, it is known that Marinucci was actively acquiring paintings in the Marche in the 1920s, possibly on behalf of his uncle.8

The dating and reconstruction of the original structure from which the Yale Saint Peter and the six other known fragments were excised have been the subject of debate since their appearance on the art market. Beginning with Franz Drey, who wrote the first monograph on Carlo Crivelli, early authors conflated several of the panels in the present grouping with another series of half-length apostles and a Blessing Redeemer that once belonged to the predella of the monumental polyptych executed by the artist between around 1471 and 1473 for the church of San Francesco in Montefiore dell’Aso (Ascoli Piceno), which was dismembered in the mid-nineteenth century and dispersed among various collections.9 A distinction between the two sets of works, however, was made by Suida, who categorically rejected any possible association between either the Yale Saint Peter or the El Paso Blessing Redeemer and the Montefiore Polyptych, arguing that the former were products of Crivelli’s maturity, datable “not earlier than 1475, possibly rather later.”10 Comparing the Yale Saint Peter to the same figure from the Montefiore Polyptych, Suida pointedly noted that “by the side of the muscular St. Peter, in violent action, with strongly marked features, who is represented before us, the figure of the Monte Fiore [sic] altarpiece looks nearly tame and feeble.”11 In a much later examination of the El Paso Redeemer, the same author maintained his original opinion, dating that work more precisely to about 1475–80.12

In 1961 Federico Zeri, who added the Milan and ex-Proehl Apostles to the Yale and El Paso panels, reiterated Suida’s distinction between this group of works and the Montefiore altarpiece but advanced a significantly earlier dating, proposing that they were elements of an as-yet-unidentified altarpiece executed around the same moment as the so-called Fesch-Erickson Polyptych (named after its former owners), another dismembered complex with, at its center, the signed and dated 1472 Virgin and Child Enthroned in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.13 Echoing Zeri’s comparison, Pietro Zampetti went a step further and incorporated the five predella panels then known to scholars, along with a Pietà in the Philadelphia Museum of Art,14 in the reconstruction of the Fesch-Erickson Polyptych.15 Zampetti’s argument was taken up, even if tentatively, by much of the subsequent scholarship, and it was most recently upheld by Stefano Casu, in his discussion of the Pittas Saint James Major.16 Keith Christiansen, however, had already questioned the likelihood of Zampetti’s reconstruction, based on the discrepancy between the combined width of the main panels in the Fesch-Erickson Polyptych (174.9 cm) and the considerably larger size (at least 230–35 cm) of a predella comprising the panels under consideration plus the presumed missing elements.17

A second hypothesis regarding the possible provenance of the present series was put forth by Anna Bovero, who cautiously suggested the fragments could have belonged to the polyptych formerly in the church of San Domenico, Ascoli Piceno, dated 1476 and currently divided between the National Gallery, London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.18 The connection made by Bovero was deemed plausible by Andrea De Marchi,19 based on both style and dimensions, but it was rejected by Mauro Minardi,20 who argued that, in the 1476 Ascoli Polyptych, as in the Fesch-Erickson altarpiece, the light source comes from the left in every section, whereas in each of the elements of the present predella it comes from the opposite side—an inconsistency that would be out of character in an altarpiece by Crivelli, where the lighting is always unified and homogeneous throughout the various parts. Minardi concluded that the fragmentary predella, perhaps along with the Philadelphia Pietà, had to be associated with a hitherto unidentified altarpiece executed by the artist between around 1473 and 1476. The same conclusion was drawn by Francesco De Carolis, who followed the traditional dating in the 1470s.21

In the most recent consideration of the issue, Federica Coltrinari22 returned to a suggestion of Ronald Lightbown,23 dismissed by later critics, and associated the predella with the signed and dated 1482 Virgin and Child with a Franciscan Friar in the Pinacoteca Vaticana (fig. 8), whose provenance can be traced to an altarpiece executed by the artist for the church of San Francesco in Force, near Ascoli Piceno. Transferred to the Vatican Museums in 1844, the Force Virgin and Child was first referred to by the Marchigian nineteenth-century historian Amico Ricci, who saw it in 1828 on one of the side altars of the Collegiata of San Paolo in Force, where it had been moved after the destruction of San Francesco. Ricci noted that the picture, signed by Crivelli, formed part of a “large triptych” (un gran trittico) once situated on the main altar of the church of San Francesco, and that “all the panels” (tutte le tavole) that originally surrounded it were dispersed and lost.24 An additional clue to the altarpiece’s structure was discovered by Coltrinari in the Archivio di Stato, Rome, in the form of an 1831 report on Force’s lost treasures, addressed to city officials by the local historian Giuseppe Maria Antonelli Rampazzi.25According to Rampazzi, the altarpiece included “two laterals as big as the Virgin and Child” (due laterali eguali alla Vergine) and “other [panels] smaller in size, which formed the base,” but only the Virgin survived miraculously intact, some of the other elements having been purportedly destroyed by the monks during the church’s demolition.26 Based on these accounts, Coltrinari proposed that the altarpiece was a double-tiered structure with a predella and added to her reconstruction, in addition to the surviving Apostles and Redeemer, the badly damaged Pietà formerly in the Caccialupi collection in Macerata, now in the Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts (fig. 9), proposing that it was the pinnacle of the dismembered complex.27

While the evidence presented by Coltrinari is not conclusive, her reconstruction of the Force altarpiece seems plausible. Previous objections to Lightbown’s association between the predella fragments and the Force altarpiece had focused partly on perceived differences in style but, above all, on the assumption that the work seen by Ricci was a traditional triptych, whose width could not have accommodated a predella with ten or twelve apostles. It must be noted, however, that Ricci used exactly the same words (un gran trittico) to describe a large polyptych he attributed to Carlo Crivelli in the Franciscan church of San Francesco in Monte San Pietrangeli, Fermo (fig. 10),28 indicating that he applied the term loosely or, at the very least, was referring to comparable structures. Commissioned from Vittore Crivelli in 1501 but completed by an unidentified local workshop between around 1502 and 1510, the Monte San Pietrangeli altarpiece includes a predella with Christ and the twelve apostles and, in the main register, a Virgin and Child flanked by pairs of standing saints on each side, separated by slender colonnettes.29 The retardataire design of the frame echoes the earlier polyptychs of Carlo and Vittore, attesting to the endurance of such models into the sixteenth century and the likelihood of a similar construction for the Force altarpiece.

Independent of the proposed association with the Force altarpiece, a date for the predella fragments in the 1480s is consistent with the significant distinctions between the handling of these figures and the artist’s approach in the previous decade. A considerable interval of time must undoubtedly separate the execution of the emaciated, haggard-looking apostles in the predella of the 1473 Sant’Emidio Polyptych (see fig. 7) and the robust, energetic figures of the Yale Saint Peter and its companions. The formal contrasts are less pronounced in the 1476 Ascoli Polyptych divided between the Metropolitan Museum and National Gallery, but even there the figures have a studied elegance that is absent from the works under consideration. The polished finish and meticulously controlled lines of the National Gallery Saint Andrew (fig. 11), for example, have given way in the ex-Proehl version (see fig. 4) to a markedly looser approach and an almost frenzied, forceful hatching technique used over the thinly painted surface. The result, even more evident in the similarly handled Yale Saint Peter, is a rough, spontaneous quality that animates the figures and increases their visual impact. Perhaps not coincidentally, a comparable technique is employed in the predella and in ancillary details of Carlo Crivelli’s signed and dated 1482 altarpiece for the church of San Domenico in Fermo, now in the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan (fig. 12).30 With their severe expressions and unruly beards, the small figures of Saint Anthony Abbot and Saint Andrew in the Brera predella are intimately related to the ex-Proehl and Yale Saints, as are the small images of apostles painted on the orphrey band of the standing Saint Peter in one of the main compartments. A panel of the Last Supper in the Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal (fig. 13), now thought to be the missing central element of the Brera predella, shares the same palette of lightly applied washes and expressive treatment of the dynamically posed figures.31

In Coltrinari’s proposed reconstruction, Crivelli’s Force altarpiece would have been a monumental structure befitting its position on the main altar of the Franciscan convent of San Francesco. It may be presumed that the diminutive figure in a Franciscan habit kneeling in prayer at the feet of the Vatican Virgin (see fig. 8) was a leading member of the community, possibly the prior who commissioned the work during his tenure. Lightbown tentatively suggested that he could be Fra Francesco da Force, a renowned master of theology and later inquisitor in Florence, who held the important office of custode of the Sacred Convent of San Francesco at Assisi ten times between 1466 and 1486 and became provincial minister of the Conventuals of the Marche in 1486, the same year he died.32 —PP

Published References

Suida, William E. “Italian Primitives in the Marinucci Collection in Rome.” Apollo 20, no. 117 (September 1934): 119–24., 122; William E. Suida, in Samuel H. Kress Collection in the Honolulu Academy of Arts. Honolulu: Honolulu Academy of Arts, 1952., 20; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Venetian School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1957., 1:70; Bovero, Anna. Tutta la pittura del Crivelli. Milan: Rizzoli, 1961., 68, 94, pl. 67a; Seymour, Charles, Jr. The Rabinowitz Collection of European Paintings. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1961., 26–27, 54; Zampetti, Pietro. Carlo Crivelli. Milan: Aldo Martello, 1961., 77, fig. 32; Zeri, Federico. “Cinque schede per Carlo Crivelli.” Arte antica e moderna 13 (1961): 158–76., 160, pl. 61b; Barbara Sweeny, in John G. Johnson Collection. Catalogue of Italian Paintings. Philadelphia: n.p., 1966., 25; Shapley, Fern Rusk. Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools, XV–XVI Century. London: Phaidon, 1968., 35–36; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 239–41, no. 180; Zampetti, Pietro. Paintings from the Marches: Gentile to Raphael. London: Phaidon, 1971., 186; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 601; Elizabeth de Fenandez-Gimenez, in European Paintings before 1500. Cleveland Museum of Art Catalogue of Paintings, Part 1. Cleveland: The Museum, 1974., 69; Bovero, Anna. L’opera completa del Crivelli. Milan: Rizzoli, 1975., 89, no. 52, fig. 52; Keith Christiansen, in The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984., 30; Zampetti, Pietro. Carlo Crivelli. Florence: Nardini, 1986., 87, 260–61, pl. 22; Gilbert, Creighton. “An Addition to Lorenzo d’Alessandro da Sanseverino.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin 40, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 20–25., 24, fig. 3; Pope-Hennessy, John, and Laurence Kanter. The Robert Lehman Collection. Vol. 1, Italian Paintings. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987., 224; Kenney, Elise K., ed. Handbook of the Collections: Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1992., 135; Lightbown, Ronald. Carlo Crivelli. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004., 303–4, fig. 126; Costanza Costanzi, in Costanzi, Costanza, ed. Le Marche disperse: Repertorio di opere d’arte dalle Marche al mondo. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2005., 145, no. 119, fig. 119; Virginia Brilliant, in European Treasures: International Gothic through Realism / Tesoros Europeos: Gótico internacional hasta el realismo. El Paso, Tex.: El Paso Museum of Art Foundation, 2010., 75; Casu, Stefano G. The Pittas Collection. Vol. 1, Early Italian Paintings (1200–1530). Florence: Mandragora, 2011., 34–35; Mauro Minardi, in Chiodo, Sonia, and Serena Padovani, eds. Italian Paintings from the 14th to 16th Century. The Alana Collection 3. Florence: Mandragora, 2014., 59, fig. 9b; Francesco De Carolis, in Campbell, Stephen J., ed. Ornament and Illusion: Carlo Crivelli of Venice. Exh. cat. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2015., 165, 173, no. 12, fig. 12; De Carolis, Francesco. “Alcune considerazioni sulla prima attività di Carlo Crivelli nelle Marche: Il dossier Crivelli nella Fondazione Zeri.” Intrecci d’arte 6, no. 6 (2017): 1–13., 12n28; Cipolletti, Carlo. “Carlo Crivelli, dalla Dalmazia alle Marche.” Marca/Marche 13 (2019): 140–67., 157; Coltrinari, Francesca. “Carlo Crivelli: La perfezione dell’arte.” In Carlo Crivelli: Le relazioni meravigliose, ed. Francesca Coltrinari and Giuliana Pascucci, 23–47. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2022., 30; De Luca, Daphne. Il polittico di Carlo Crivelli a Montefiore Dell’Aso. 2nd ed. Florence: Edifir, 2023., 14, 36, 138, 142, fig. 21

Notes

-

According to information on a reproduction in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York. No date is provided. ↩︎

-

A note written by Creighton Gilbert on September 10, 1988, reports that he had just been informed in a postcard from Henck van Os that the ex-Proehl painting had recently belonged to “Mr. Lemberger in Amsterdam”; curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

Sale, Sotheby’s, New York, February 21, 2024, lot 302. ↩︎

-

For the most detailed study to date of the Sant’Emidio Polyptych, see Lightbown, Ronald. Carlo Crivelli. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004., 143–83. For the Monte San Martino Polyptych, currently thought to be a workshop product involving other hands as well as those of the Crivelli brothers, see Delpriori, Alessandro. “Carlo Crivelli nelle Marche: Un percorso tra dare e avere.” In Opus Karoli Crivelli: Le opera e la materia; Nuove letture su Carlo Crivelli, ed. Daphne De Luca et al., 129–50. Ascoli Piceno: Capponi, 2022. (with previous bibliography). According to Alessandro Delpriori, the polyptych was begun by Carlo around 1481–82 and completed by Vittore a decade later. ↩︎

-

Suida, William E. “Italian Primitives in the Marinucci Collection in Rome.” Apollo 20, no. 117 (September 1934): 119–24., 122. ↩︎

-

The letter, written from Rome on October 1, 1936, is in the curatorial files for Tanzio da Varallo’s Saint John the Baptist in the Wilderness in the Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, Oklahoma, inv. no. 1944.2. Its existence was uncovered by Nancy H. Yeide; see Yeide, Nancy H. “Princes, Dukes, and Counts: Pedigrees and Problems in the Kress Collection.” Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals 10, no. 3 (Summer 2014): 265–72., 268–69. The Tanzio da Varallo was among a group of ten paintings and one drawing that Marinucci was offering for sale to settle the estate of his uncle. I am grateful to the curatorial staff at the Philbrook for forwarding me a scan of the letter and attached list of works, which are described as follows: “1. Tiziano-Ritratto Senatore Veneto; 2. Tiziano-Ritratto Solimano; 3. Dosso Dossi-San Giovannino [Tulsa Saint John the Baptist]; 4. Ingres-Ritratto di Letizia Bonaparte; 5. Crivelli-Pietà; 6. Correggio-Madonna del Latte; 7. Beccafumi-Sacra Famiglia [now National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., inv. no. 1943.4.28, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.12126.html]; 8. Rubens-Bozzetto Quattro Evangelisti; 9. Carpaccio-Sant’Orsola con donatore [now Lazzaro Bastiani, Portland Art Museum, Oregon, inv. no. 61.45]; 10. Antonello-Ritratto Maria Sforza Duca d . . . ; Scuola senese-Piccola Crocifissione [now Allegretto Nuzi, Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama, inv. no. 1961.113].” Four of these pictures, including the Tanzio da Varallo, are mentioned in Suida’s 1934 article on the Marinucci collection. They were purchased by the famous Florentine dealer Count Alessandro Contini Bonacossi (1878–1955), who sold them to Samuel H. Kress (1863–1955) in 1939. As noted by Yeide, it is not out of the question that Contini Bonacossi bought the entire Marinucci collection. The El Paso Redeemer had already been purchased by Contini Bonacossi sometime between 1934 and 1935, when it was part of an earlier group of works sold by Contini Bonacossi to Kress; see Kress Collection Digital Archive, Contini Bonacossi invoice dated July 10, 1935, https://kress.nga.gov/Detail/acquisitions/ACQ145). It was gifted to the El Paso Museum of Art in 1961; see Shapley, Fern Rusk. Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools, XV–XVI Century. London: Phaidon, 1968., 35–36. There are no surviving records for the Yale panel predating its entry into the Rabinowitz collection, but it seems reasonable to hypothesize that it was acquired by Contini Bonacossi along with the Redeemer. ↩︎

-

Gasparri was born in Ussita, in the province of Macerata, and continued to have close ties to the region. According to his wishes, he was buried in the small cemetery in Ussita, where there is a museum in his name. For a contemporary portrait of the cardinal, see Littlefield, Walter. “Cardinal Gasparri.” Current History 32, no. 1 (1930): 53–58., 53–58. ↩︎

-

In 1929 Marinucci offered to buy from the nuns of the Clarissan convent of Santa Chiara in Sanseverino Marche a fourteenth-century Virgin of Humility by Catarino da Venezia. See Paciaroni, Raoul. “Per la storia di un perduto dipinto sanseverinate del XIV secolo.” Arte Marchigiana 5 (2017): 11–22., 16–17, where Raoul Paciaroni postulated that the final buyer of the panel (now lost) was Contini Bonacossi, who had offered a larger sum than Marinucci. ↩︎

-

Drey, Franz. Carlo Crivelli und seine Schule. Munich: G. F. Bruckmann, 1927., 126–27. Drey connected the Milan and ex-Proehl Apostles to other panels now recognized as part of the Montefiore predella. He was followed by Raimond van Marle (in van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 18. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1936., 13), who added the Yale and El Paso paintings to the same grouping. In the 1935 invoice of his sale to Kress (see note 6, above), Contini Bonacossi listed the El Paso Redeemer—alongside the two ex-Montefiore Apostles now in the Honolulu Museum of Arts, inv. nos. 2979.1, 2980.1 (https://honolulu.emuseum.com/objects/35161/an-apostle; https://honolulu.emuseum.com/objects/35162/an-apostle; and see Shapley, Fern Rusk. Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools, XV–XVI Century. London: Phaidon, 1968., 36)—as having been part of the same complex. For the intricate history of the dismemberment and reconstruction of the Montefiore altarpiece, see the recent monograph by Daphne De Luca; De Luca, Daphne. Il polittico di Carlo Crivelli a Montefiore Dell’Aso. 2nd ed. Florence: Edifir, 2023. (with previous bibliography). ↩︎

-

Suida, William E. “Italian Primitives in the Marinucci Collection in Rome.” Apollo 20, no. 117 (September 1934): 119–24., 122. ↩︎

-

Suida, William E. “Italian Primitives in the Marinucci Collection in Rome.” Apollo 20, no. 117 (September 1934): 119–24., 122. ↩︎

-

William E. Suida, in Samuel H. Kress Collection in the Honolulu Academy of Arts. Honolulu: Honolulu Academy of Arts, 1952., 20. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1982.60.5, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436051. See Zeri, Federico. “Cinque schede per Carlo Crivelli.” Arte antica e moderna 13 (1961): 158–76., 162. The main register of that polyptych included, alongside the Metropolitan Virgin and Child, a Saint Dominic and a Saint George, also in the Metropolitan (inv. nos. 05.41.1–.2, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436054; and https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/438691), a Saint James Major in the Brooklyn Museum (inv. no. 78.151.10, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/4847), and a Saint Nicholas of Bari in the Cleveland Museum of Art (inv. no. 1952.111, https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1952.111). See Keith Christiansen, in The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984., 29–32 (with previous bibliography); and Lightbown, Ronald. Carlo Crivelli. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004., 127–37. ↩︎

-

John G. Johnson Collection, inv. no. cat. 158, https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/101897. ↩︎

-

Zampetti, Pietro. Carlo Crivelli. Milan: Aldo Martello, 1961., 77; and Zampetti, Pietro. Carlo Crivelli. Florence: Nardini, 1986., 260–62, nos. 20–24. ↩︎

-

Casu, Stefano G. The Pittas Collection. Vol. 1, Early Italian Paintings (1200–1530). Florence: Mandragora, 2011.. The Pittas Saint James was first recognized as part of the series by Zeri; see Zeri, Federico. “Un’Adorazione dei Magi di Vittorio Crivelli.” In Diari di Lavoro, 2:71–75. Turin: Giulio Einaudi, 1976., 75. Casu also alluded to the recent appearance on the art market (Christie’s, New York, January 26, 2001, lot 8) of a seventh panel, the Apostle formerly in the Alana Collection, subsequently published in Mauro Minardi, in Chiodo, Sonia, and Serena Padovani, eds. Italian Paintings from the 14th to 16th Century. The Alana Collection 3. Florence: Mandragora, 2014., 59–66, no. 9. ↩︎

-

Christiansen, in The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984., 30–31. As noted by Minardi (in Chiodo, Sonia, and Serena Padovani, eds. Italian Paintings from the 14th to 16th Century. The Alana Collection 3. Florence: Mandragora, 2014., 62), the combined width of a predella with ten apostles, as in the Sant’Emidio Polyptych, would have been no less than 230 to 235 centimeters, not including the carpentry. With twelve apostles, as in the Monte San Martino Polyptych, it would have been at least 270 to 280 centimeters. ↩︎

-

Bovero, Anna. Tutta la pittura del Crivelli. Milan: Rizzoli, 1961., 68. Formerly known as the Demidoff Polyptych, the altarpiece was a double-tiered polyptych, the remainders of which consist of nine panels in the National Gallery of Art, London (inv. nos. NG788.1–.9, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/carlo-crivelli-the-demidoff-altarpiece#painting-group-info), and a Pietà in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (inv. no. 13.178, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436053). See Baker, Christopher, and Tom Henry. The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue. London: National Gallery, 1995., 160–61; and Lightbown, Ronald. Carlo Crivelli. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004., 208–225. ↩︎

-

Andrea De Marchi, written correspondence to the Sarti Gallery, cited by Minardi, in Chiodo, Sonia, and Serena Padovani, eds. Italian Paintings from the 14th to 16th Century. The Alana Collection 3. Florence: Mandragora, 2014., 60. ↩︎

-

Minardi, in Chiodo, Sonia, and Serena Padovani, eds. Italian Paintings from the 14th to 16th Century. The Alana Collection 3. Florence: Mandragora, 2014., 62–63. ↩︎

-

Francesco De Carolis, in Campbell, Stephen J., ed. Ornament and Illusion: Carlo Crivelli of Venice. Exh. cat. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2015., 173; and De Carolis, Francesco. “Alcune considerazioni sulla prima attività di Carlo Crivelli nelle Marche: Il dossier Crivelli nella Fondazione Zeri.” Intrecci d’arte 6, no. 6 (2017): 1–13., 12n28. ↩︎

-

Coltrinari, Francesca. “Carlo Crivelli: La perfezione dell’arte.” In Carlo Crivelli: Le relazioni meravigliose, ed. Francesca Coltrinari and Giuliana Pascucci, 23–47. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2022., 28–30. ↩︎

-

Lightbown, Ronald. Carlo Crivelli. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004., 303–5. ↩︎

-

“Force, Collegiata. Nella prima cappella entrando a mano sinistra rimane in luogo altissimo una tavola con la Vergine, ed il Bambino, e sotto vi si sottoscrisse Opus Caroli Crivelli. Questa tavola formava parte di un gran trittico che rimaneva nel maggiore altare della Chiesa di San Francesco oggi diruta. Tutte le tavole che contornavano l’attuale furono tutte disperse e smarrite.” Amico Ricci, “Viaggio per i vari paesi della nostra montagna eseguito nel settembre 1828,” Biblioteca Mozzi Borgetti, Macerata, Fondo Ricci, MS 1062-I, fol. 203v; and Ricci, Amico. Memorie storiche delle arti e degli artisti della Marca di Ancona. 2 vols. Macerata: Alessandro Mancini, 1834., 1:209. The relevant passage of the “Viaggio” was first published by Lightbown, Ronald. Carlo Crivelli. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004., “Appendix IV,” 508. The full manuscript was later edited by Anna Maria Ambrosini Massari, with the collaboration of Elisa Barchiesi; see Ambrosini Massari, Anna Maria, with Elisa Barchiesi. “Amico Ricci: Viaggio per i vari paesi della nostra montagna eseguito nel settembre 1828.” In “Dotti Amici”: Amico Ricci e la nascita della storia dell’arte nelle Marche, ed. Anna Maria Ambrosini Massari, 513–32. Ancona: Il Lavoro, 2007., 513–32, esp. 527–28. ↩︎

-

Coltrinari, Francesca. “Carlo Crivelli: La perfezione dell’arte.” In Carlo Crivelli: Le relazioni meravigliose, ed. Francesca Coltrinari and Giuliana Pascucci, 23–47. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2022., 28, 44n35. ↩︎

-

Coltrinari, Francesca. “Carlo Crivelli: La perfezione dell’arte.” In Carlo Crivelli: Le relazioni meravigliose, ed. Francesca Coltrinari and Giuliana Pascucci, 23–47. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2022., 44n35. Rampazzi wrote that some of the panels were “sacrificed to the most vile uses and even barbarously [given] to the flames” (sacrificati ad usi vilissimi ed anche barbaramente alle fiamme), a fact that would appear to contradict Ricci’s claim that they were all dispersed and lost. ↩︎

-

Coltrinari, Francesca. “Carlo Crivelli: La perfezione dell’arte.” In Carlo Crivelli: Le relazioni meravigliose, ed. Francesca Coltrinari and Giuliana Pascucci, 23–47. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2022., 29–30, 132–33, no. 2. The possibility of this work having been part of the same altarpiece as the Force Virgin and Child, with which it shares the same source of light from the right and the same punches, was first raised by Minardi (Minardi, Mauro. “Studi sulla collezione Nevin: I dipinti veneti del XIV e XV secolo.” Saggi e memorie di storia dell’arte 36 (2012): 315–50., 349–50n136). Past efforts to connect the Harvard panel to a Virgin and Child in the Musei Civici di Palazzo Buonaccorsi, Macerata, inv. no. 35, as noted by Coltrinari, can be dismissed on the basis of new technical studies that confirm it was originally painted on canvas; see De Luca, Daphne. “Il dipinto su tela di Carlo Crivelli a Palazzo Buonaccorsi. Sorprendenti novità tecniche e materiche in seguito al restauro.” In Carlo Crivelli: Le relazioni meravigliose, ed. Francesca Coltrinari and Giuliana Pascucci, 59–67. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2022., 59–67. ↩︎

-

“Ed in fine per lavoro suo [Carlo Crivelli’s] ritenni un gran trittico, che appeso nel mezzo della Chiesa dei Francescani, vedesi nella terra di Monte-Sampietrangeli.” Ricci, Amico. Memorie storiche delle arti e degli artisti della Marca di Ancona. 2 vols. Macerata: Alessandro Mancini, 1834., 210. ↩︎

-

For the latest discussion of the altarpiece, following its restoration in 2019, see Claudio Maggini, in Moriconi, Pierluigi, and Stefano Papetti, eds. Rinascimento Marchigiano: Opere d’arte restaurate dai luoghi del Sisma. Exh. cat. Ancona: Errebi Grafiche Ripesi, 2019., 64–69. ↩︎

-

For a reconstruction of the Brera altarpiece, see, most recently, Anna Jolly, in Daffra, Emanuela, ed. Crivelli e Brera. Exh. cat. Milan: Electa, 2009., 136–49, no. 1; and Stephen J. Campbell, in Campbell, Stephen J., ed. Ornament and Illusion: Carlo Crivelli of Venice. Exh. cat. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2015., 183–89, nos. 17–18. ↩︎

-

The Montreal panel was first associated with the complex by Robert B. Simon, in Daffra, Emanuela, ed. Crivelli e Brera. Exh. cat. Milan: Electa, 2009., 150–53, no. 2. ↩︎

-

Lightbown, Ronald. Carlo Crivelli. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004., 302–3. As recently argued by Stefano Papetti (in Papetti, Stefano. “Il mercato dell’arte fra le Marche e Roma nel primo Ottocento.” In Carlo Crivelli: Le relazioni meravigliose, ed. Francesca Coltrinari and Giuliana Pascucci, 97–105. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2022., 101–3), Francesco da Force may also have commissioned the small Pietà by Crivelli now in the Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. no. MI 489, https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010065008—a work that can plausibly be linked to the record of a “small Carlo Crivelli . . . showing the Deposed Christ” that was bought in Force by Ignazio Cantalamessa and sold in Rome in 1826–27. An incomplete citation of the same source by Giannino Gagliardi, who refers simply to an image of “Christ” (Gagliardi, Giannino. L’Annunciazione di Carlo Crivelli ad Ascoli. Ascoli Piceno: Giannino e Giuseppe Gagliardi, 1996., 5), prompted Lightbown (in Lightbown, Ronald. Carlo Crivelli. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004., 302) to associate this work with the El Paso Redeemer, which clearly shows a different subject. The original document, published in full by Papetti (in Papetti, Stefano. “Il mercato dell’arte fra le Marche e Roma nel primo Ottocento.” In Carlo Crivelli: Le relazioni meravigliose, ed. Francesca Coltrinari and Giuliana Pascucci, 97–105. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2022., 105), is a record of all the purchases made by Cantalamessa in the Marche and sold by him in Rome in 1826–27. Also listed are “ten panels” bought from “the canons in Force.” Although neither the artist nor the subject matter are specified in the entry, it is worth speculating whether any of those works were fragments of the Force altarpiece’s predella. ↩︎