Edwin Austin Abbey (1852–1911), London, by 1911;1 Estate of Edwin Austin Abbey, by 1931

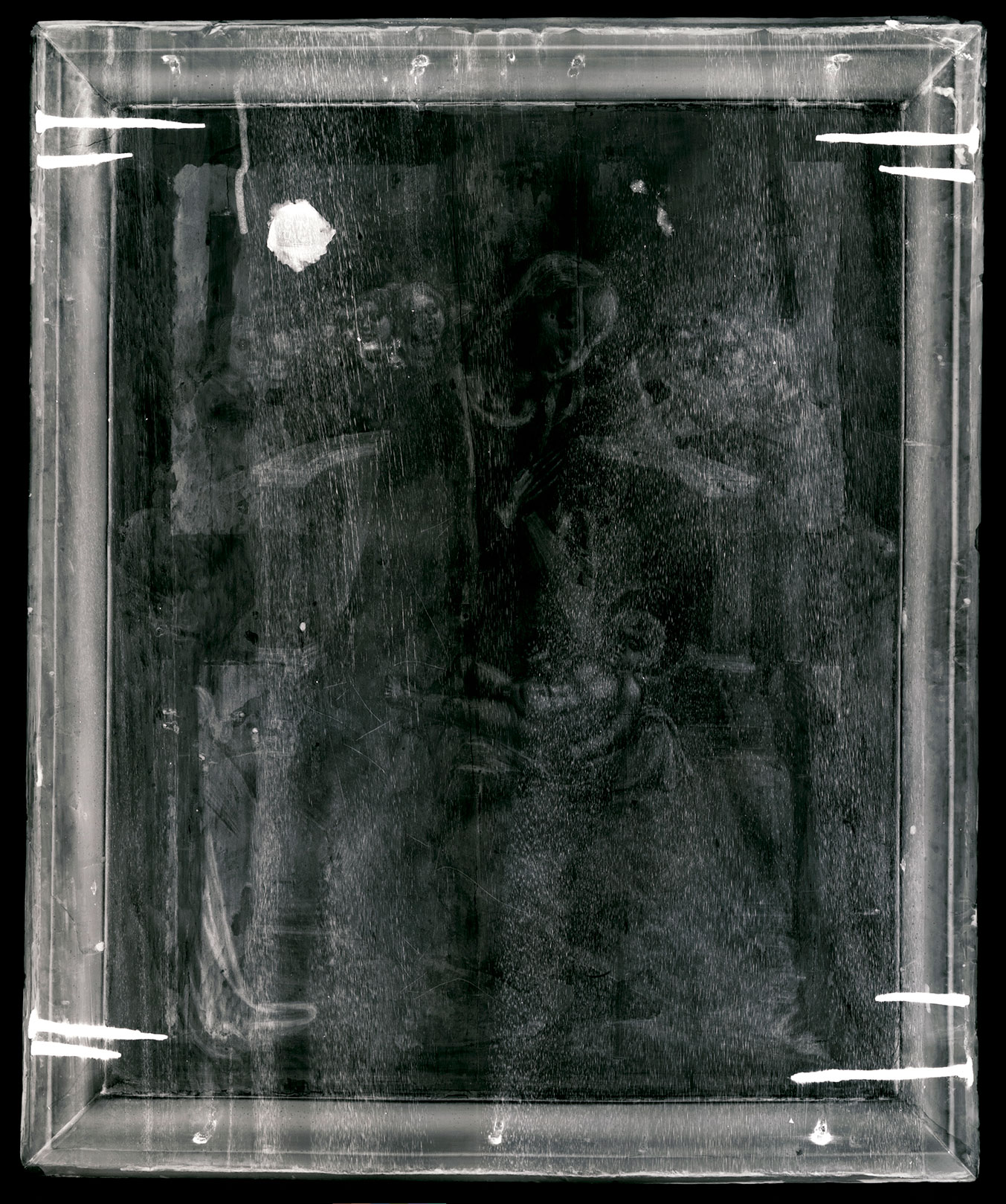

The panel support, of a vertical wood grain, retains what appears to be its original thickness of only 9 millimeters and has not been cradled. An old but not original wooden stretcher glued and nailed to the reverse was removed during treatment at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, in 1999–2000, and four partial splits, 11.5, 12.5, 16.5, and 25.5 centimeters from the left edge (seen from the front), were repaired by Gianni Marussich at that time. The frame moldings applied to all four sides of the panel appear to be original but are regilt, and only the bottom molding appears not to have been disturbed: the bottom edge of the panel shows no evidence of having been cut, and a barb of gesso eliding the picture surface to the frame molding along the bottom is unbroken. Both side moldings appear to have been removed from the panel at some point, the panel cut by approximately 12 to 15 millimeters on each side and the moldings reapplied. X-radiographs (fig. 1) show that the paint surface continues beneath the reengaged frame along the sides and that the original nails securing the 1.5-centimeter-wide capping strips of the frame were removed and repositioned. There is no barb of gesso or paint at either lateral edge of the picture surface, and the gilding along the top edge has been shaved well shy of the present position of the frame there. The back edge of the capping strips along all four edges have been cut flush with back of the panel. Two holes drilled through the top edge of the frame and back of the panel to accommodate a hanging strap date from the repositioning of the frame moldings.

The gilding and paint surfaces have been heavily abraded and extensively repaired. Large patches of new gold and smaller local retouches with shell gold were applied by Elizabeth Mention during the cleaning of 1999–2000, but the overall continuity of the gold ground contrasted with the much-deteriorated state of the Virgin’s halo suggests that the ground may have been releafed at an early date, possibly when the panel was reduced in size and the frame regilt. If so, it may be assumed that the wings and coarse, stippled haloes of the angels are later additions. Paint and gilding losses along the four splits in the panel have been repaired, as have extensive local losses of paint, especially in the draperies of the first angel at the left and the first and third angels at the right; in the draperies and head of the Virgin; and in the body of the Christ Child. The faces of all the angels have been repainted, and many of the hands, of all the figures, are reinvented, though not necessarily in modern times.

Attributed by Charles Seymour, Jr., to an unidentified Florentine painter2 and then assigned to Niccolò Alunno (active ca. 1456–1502),3 the Yale Virgin and Child with Saints Peter Martyr and Vincent Ferrer(?) and Adoring Angels was first recognized by Creighton Gilbert as the work of Lorenzo d’Alessandro da Sanseverino4—a personality described by Bernard Berenson as “the best known artist, after Gentile da Fabriano, in the Marches”5 but overlooked by modern scholarship until relatively recent times.6 Despite the losses and the abrasions of the original surface, the small panel still manages to convey the charming qualities and delicate handling that prompted Berenson’s appreciative judgment of the painter. The composition, as noted by past scholars, is indebted to the models of Niccolò Alunno and especially to the so-called Madonna dei Consoli in the Pinacoteca Comunale, Deruta, but also, and in more profound ways, to the example of Lorenzo’s older contemporary Luca di Paolo da Matelica (ca. 1435–1490), with whom the artist collaborated in the 1470s.7 The Virgin and Child in Luca di Paolo’s double-sided banner in the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria, Perugia (fig. 2), dated by recent studies between 1470 and 1475,8 provides the closest precedent for the Yale panel in both the type of Madonna and structure of the throne. The Late Gothic sensibility of Luca di Paolo, however, has been replaced in the Yale Virgin and Child by a more rational approach and spatial concerns that denote a fully developed Renaissance vision.

As in earlier examples, the Yale image is organized around the Virgin’s semicircular throne, but in the present instance, the monumental solidity of the classically inspired architectural components adds spatial depth and breadth to the composition. Still discernible are the fluting in the white marble of the throne’s back and the interstices of the black cornice, as well as the carved rectangular sections on the front of the seat, all of which emphasize the three-dimensionality of the structure. The Virgin is seated at an angle, her body turned slightly to the left and casting a light shadow on the curvature of the throne behind her. Her hands crossed in prayer, she is shown meditating on the future fate of the naked Christ Child lying on a white shroud over her lap—a motif that anticipates the iconography of the Pietà and Lamentation. Sensitively applied highlights define the delicate folds and fringed ends of the ceremonial cloth. The Virgin wears a blue mantle over a lavender tunic. In highlighted sections of the dress, the lavender paint is broken through by small parallel incisions to reveal the layer of silver leaf applied below it (now darkened to black)—a technique first found in the work of Gentile da Fabriano and intended to achieve different luminous and textural effects.9 Inscribed on the Virgin’s halo are the beginning words of the Marian hymn “AVE MARI[S] STELLA” (Hail, star of the sea).

Kneeling in adoration before the Virgin and Child are two saints wearing the Dominican habit. On the left is Saint Peter Martyr, recognizable by the traditional attribute of a knife in his head. The saint on the right, thought by Seymour to be Saint Antoninus, was identified by Luisa Vertova as Saint Vincent Ferrer, a celebrated Spanish theologian and Dominican preacher who became an object of popular devotion soon after his death in 1419 and who was canonized in 1455.10 Known for his fiery sermons on the Apocalypse, the saint is traditionally represented according to the iconographic type codified at his process of canonization, holding a book open to verse 14:7 from the Book of Revelations: “TIME / TE. D / EUM / ET.D / ATE / ILLI. / ONO / REM / QUIA / VENI[T]” (Fear God and give him honor for [the hour of judgment] has come).11 X-radiographs of the Yale painting, however, reveal that the book held by the saint is a later, perhaps even modern, addition and that the figure originally had one arm extended upward (see fig. 1).12 If this is indeed Vincent Ferrer, it is possible that the depiction followed an iconographic variant, with the saint shown pointing up to a small image of Christ as the Last Judge while holding a book in his other hand. In images where the Revelations text is included, the figure of Christ is sometimes omitted, as in Niccolò Alunno’s dynamically posed version of the preacher, with extended arm and open book, among the pilaster saints of the Montelparo Polyptych, now in the Pinacoteca Vaticana.13 In still other instances, both Christ and the book are absent, and the saint simply points up to a banderole inscribed with the biblical verses associated with him.14 It is impossible to determine what formula was originally followed in the present picture or to dismiss the uncertainties about the saint’s identity. Nevertheless, the apocalyptic message of Vincent Ferrer would seem to be reinforced by the twelve angels (counting the inscribed haloes of those whose heads are not visible) standing against the gold background behind the Virgin’s throne—possibly a reference to the twelve angels that guarded God’s kingdom in the Book of Revelations (21:12).

Gilbert’s attribution of the Yale painting to Lorenzo d’Alessandro was based on its stylistic relationship to the signed Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine in the National Gallery, London (fig. 3), executed for the church of San Domenico in Fabriano and generally considered one of the crowning achievements of the artist’s career. A terminus post quem for the execution of that work is given by the presence of the Blessed Costanzo da Fabriano, who died in 1481 and is shown kneeling in adoration to the right of the Virgin.15 Based on perceived affinities with Signorelli’s 1484 altarpiece for the duomo in Perugia, the Mystic Marriage has been dated between 1481 and 1484 by some authors,16 but a later chronology in the second half of the decade is more likely.17 The animated gestures and postures of the London figures, as well as the metallic handling of the draperies, denote a new expressive approach, consistent with a more advanced moment in the artist’s career, influenced by the late works of Carlo Crivelli.

Although distinguished by a less agitated atmosphere, the Yale Virgin and Child shares many of the same formal elements of the London painting, especially in the nuanced handling of the Virgin’s features and those of the angels in the background of the composition, but the abraded condition of the Yale panel and its modern alterations prevent more detailed comparisons. Mauro Minardi, who dated the Yale picture between 1480 and 1485,18 preferred to highlight its relationship to the much-admired 1483 frescoes in the church of Santa Maria di Piazza Alta in Sarnano, but the correspondences between these two works are confined primarily to shared compositional elements. Stylistically, the frescoes are distinguished by a less nuanced modeling technique and a greater linear emphasis that is especially evident in some of the figural types, like the Virgin and Saint Sebastian, which are directly descended from the models of the previous decade. A date for the Yale Virgin and Child sometime after the Sarnano frescoes and before the London Mystic Marriage, around the middle of the decade or slightly later, seems more accurate.

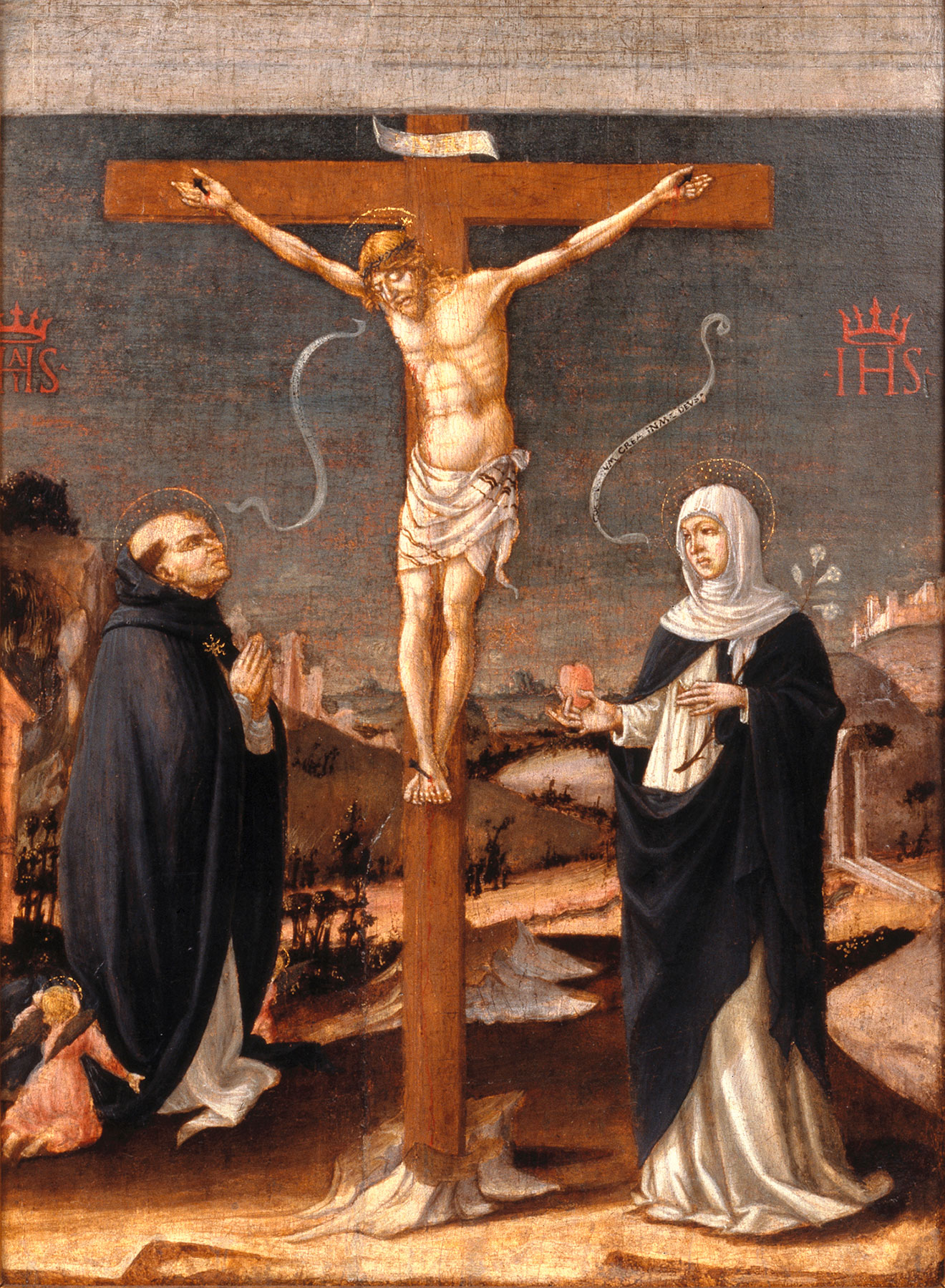

Although classified by past authors as an object for private devotion, the size and format of the Yale painting and the thinness of its panel support argue for the possibility that it could have been one face of a double-sided processional standard. Its dimensions are consistent with those of a standard by Lorenzo d’Alessandro in the Brooklyn Museum, New York (figs. 4–5), showing Christ on the Cross with Saints Thomas Aquinas and Catherine of Siena on one side and Saint Dominic protecting the female members of a confraternity on the other. Datable to the 1490s, the Brooklyn panel, similarly trimmed on all sides and presently inserted into a modern frame, was originally thought by Gilbert to be a pendant to the Yale Virgin and Child, possibly executed at a later date for the same Dominican institution.19 Based on archival and iconographic evidence, Raoul Paciaroni hypothesized that the Brooklyn picture was painted for a confraternity of Dominican tertiaries dedicated to the Rosary and located in the church of San Domenico in Sanseverino, for which the artist had completed at least two other commissions.20 As pointed out in recent studies, the Brooklyn standard belongs to a typology, characterized by a rectangular shape and smaller dimensions, that seems particular to the Sanseverino area.21 Another example, also painted by Lorenzo d’Alessandro, is in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore and was probably executed for a confraternity in Matelica, near Sanseverino.22 Three others were executed by Bernardino di Mariotto (1478–1566) around the beginning of the sixteenth century, for confraternities in Sanseverino proper. Two of these are presently divided between the Pinacoteca Vaticana, and the Galleria Giorgio Franchetti alla Cà d’Oro, Venice;23 and between the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica di Palazzo Barberini, Rome, and the Accademia Carrara, Bergamo.24 A third example, which shares the dimensions of Lorenzo d’Alessandro Virgin and Child, is in the Yale University Art Gallery.25

There are no records of the Yale Virgin and Child prior to its entering the collection of Edwin Austin Abbey, in London. Paciaroni proposed that, like the Brooklyn standard, it might also have been executed for the church of San Domenico in Sanseverino, where there was a private altar dedicated to Saint Peter Martyr and a chapel commissioned by the friars in 1459 in honor of Saint Vincent Ferrer.26 Notwithstanding the doubts regarding the identity of the saint presumed until now to be Vincent Ferrer, Paciaroni’s hypothesis should not be dismissed. If the Yale panel was part of a processional standard—a suggestion that remains tentative at present—it could have been executed for a different confraternity in San Domenico or for another Dominican establishment in the same territory. —PP

Published References

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 138–39, 314, no. 97; Vertova, Luisa. “The New Yale Catalogue.” Burlington Magazine 115 (March 1973): 159–61, 163., 160, fig. 16; Vertova, Luisa. “The Earliest Known Painting by Nicolò d Foligno.” In Studies in Late Medieval and Renaissance Painting in Honor of Millard Meiss, 2 vols, ed. Irving Lavin and John Plummer, 1:455–61, 2:157–60. New York: New York University Press, 1977., 1:455–61, 2:157, fig. 1; Gilbert, Creighton. “An Addition to Lorenzo d’Alessandro da Sanseverino.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin 40, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 20–25., 20–25, fig. 1; Donnini, Giampiero. “Lorenzo d’Alessandro da San Severino: La vocazione luministica e toscana di un pittore gotico alle soglie del Rinascimento.” In I pittori del Rinascimento a Sanseverino: Lorenzo d’Alessandro e Ludovico Urbani, Niccolò Alunno, Vittore Crivelli e il Pinturicchio, ed. Vittorio Sgarbi and Stefano Papetti, 39–52. Exh. cat. Milan: Federico Motta, 2001., 48; Paciaroni, Raoul. Lorenzo d’Alessandro detto il Severinate: Memorie e documenti. Milan: Federico Motta, 2001., 56n34, 115–16; Chui, Sue Ann. “Lorenzo d’Alessandro da Sanseverino’s Crucifixion; St. Michael: Art Historical Context and Technical Analysis of an Italian Fifteenth-Century Double-Sided Processional Standard.” Journal of the Walters Museum 63 (2005): 41–56., 50, 54, 55n1; Mauro Minardi, in Costanzi, Costanza, ed. Le Marche disperse: Repertorio di opere d’arte dalle Marche al mondo. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2005., 192, no. 255, pl. 129; Minardi, Mauro. “Nuove Acquisizioni: Su Lorenzo d’Alessandro e i suoi compagni.” Paragone, 3rd ser., 56, no. 62 (665) (July 2005): 3–29., 22n23; Calvé Mascarell, Óscar. “La configuración de la imagen de san Vicente Ferrer en el siglo XV.” 2 vols. Ph.D. diss., Universitat de València, Spain, 2016., 2:848, fig. 193

Notes

-

On the back of the panel is an inventory number, “77,” in red paint. Applied over this is an unidentified red wax seal with the letters “C.M / D.G” inside a rectangle. As pointed out by Emanuele Zappasodi (in an email dated November 11, 2010, curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery), the same seal appears on the reverse of Giovanni Baronzio’s Execution of Saint John the Baptist panel in the Robert Lehman Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (inv. no. 1975.1.103, https://www.metmuseum

.org ). A second seal on that painting bears the arms of the Conti Agnelli di Malerbi of Lugo (Ravenna). There was also another seal on the back of the Yale panel, but it has been scraped away. ↩︎/art /collection /search /459045 -

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 138–39. ↩︎

-

Vertova, Luisa. “The Earliest Known Painting by Nicolò d Foligno.” In Studies in Late Medieval and Renaissance Painting in Honor of Millard Meiss, 2 vols, ed. Irving Lavin and John Plummer, 1:455–61, 2:157–60. New York: New York University Press, 1977., 1:455–61, 2:157, fig. 1. ↩︎

-

Gilbert, Creighton. “An Addition to Lorenzo d’Alessandro da Sanseverino.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin 40, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 20–25., 20–25, fig. 1. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Catalogue of a Collection of Paintings and Some Art Objects. Vol. 1, Italian Paintings. Philadelphia: John G. Johnson, 1913., 77. ↩︎

-

Raoul Paciaroni’s 2001 volume was the first monographic study of the painter; see Paciaroni, Raoul. Lorenzo d’Alessandro detto il Severinate: Memorie e documenti. Milan: Federico Motta, 2001.. ↩︎

-

On Luca di Paolo, an artist formerly confused with the elusive Francesco di Gentile da Fabriano, see Mazzalupi, Matteo. “Luca di Paolo da Matelica, o le sorprese degli archivi.” In Luca di Paolo e il Rinascimento nelle Marche, ed. Alessandro Delpriori, 35–46. Exh. cat. Perugia: Quattroemme, 2015., 35–46 (with previous bibliography). The contacts between Luca di Paolo and Lorenzo d’Alessandro are documented by their business interactions between 1471 and 1476, although the exact nature of their relationship remains unclear. Following an intuition of Mauro Minardi (in Minardi, Mauro. “Nuove Acquisizioni: Su Lorenzo d’Alessandro e i suoi compagni.” Paragone, 3rd ser., 56, no. 62 (665) (July 2005): 3–29., 12–14), Alessandro Delpriori identified a triptych with the Crucifixion in the Museo Piersanti in Matelica as a product of their collaboration and as possible proof that Lorenzo trained in the older artist’s workshop; see Delpriori, Alessandro. “Percorso per un Rinascimento dell’Appenino.” In Vittore Crivelli da Venezia alle Marche: Maestri del Rinascimento nell’Appennino, ed. Francesca Coltrinari and Alessandro Delpriori, 23–36. Exh. cat. Venice: Marsilio, 2011., 25. For the Matelica triptych, now generally attributed to Luca di Paolo with the assistance of Lorenzo d’Alessandro, see, most recently, Spina, Giulia. “Un’opera in compagnia: Luca di Paolo e Lorenzo d’Alessandro nel trittico della Pieve di Matelica.” In Luca di Paolo e Lorenzo d’Alessandro: Stile, tecnica e restauro del trittico degli Ottoni al Museo Piersanti di Matelica, ed. Alessandro Delpriori and Giulia Spina, 27–42. Perugia: Quattroemme, 2020., 27–42 (with a summary of documents and previous opinions). Spina dates the triptych between 1470 and 1475. ↩︎

-

Delpriori, Alessandro. “Percorso per un Rinascimento dell’Appenino.” In Vittore Crivelli da Venezia alle Marche: Maestri del Rinascimento nell’Appennino, ed. Francesca Coltrinari and Alessandro Delpriori, 23–36. Exh. cat. Venice: Marsilio, 2011., 106–7, no. 2; and Garibaldi, Vittoria. Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria: Dipinti e sculture dal XII al XV secolo; Catalogo generale I. Perugia: Quattroemme, 2015., 479–81, no. 180. ↩︎

-

See, for example, Yale University Art Gallery, inv. no. 1871.66, https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/327. For an analysis of Lorenzo d’Alessandro’s painting technique, see Chui, Sue Ann. “Lorenzo d’Alessandro da Sanseverino’s Crucifixion; St. Michael: Art Historical Context and Technical Analysis of an Italian Fifteenth-Century Double-Sided Processional Standard.” Journal of the Walters Museum 63 (2005): 41–56., 48–54. ↩︎

-

Vertova, Luisa. “The Earliest Known Painting by Nicolò d Foligno.” In Studies in Late Medieval and Renaissance Painting in Honor of Millard Meiss, 2 vols, ed. Irving Lavin and John Plummer, 1:455–61, 2:157–60. New York: New York University Press, 1977., 1:455–58. ↩︎

-

For the development of this iconography, see, most recently, Calvé Mascarell, Óscar. “La configuración de la imagen de san Vicente Ferrer en el siglo XV.” 2 vols. Ph.D. diss., Universitat de València, Spain, 2016., 1:349–429, 2:433–44. ↩︎

-

This discovery undermines Vertova’s hypothesis, based on a reading of the date “1440” in the saint’s book, that this is the earliest-known work by Niccolò Alunno; see Vertova, Luisa. “The Earliest Known Painting by Nicolò d Foligno.” In Studies in Late Medieval and Renaissance Painting in Honor of Millard Meiss, 2 vols, ed. Irving Lavin and John Plummer, 1:455–61, 2:157–60. New York: New York University Press, 1977., 1:455–61. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 40307, https://catalogo.museivaticani.va

/index.php . ↩︎/Detail /objects /MV.40307 .0 .0 -

For all the possible variants, see the near-exhaustive repertory of images in Calvé Mascarell, Óscar. “La configuración de la imagen de san Vicente Ferrer en el siglo XV.” 2 vols. Ph.D. diss., Universitat de València, Spain, 2016., 2:697–872. ↩︎

-

Davies, Martin. National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools. 2nd rev. ed., London: National Gallery, 1961., 314–15, no. 249. ↩︎

-

See Donnini, Giampiero. “Lorenzo d’Alessandro da San Severino: La vocazione luministica e toscana di un pittore gotico alle soglie del Rinascimento.” In I pittori del Rinascimento a Sanseverino: Lorenzo d’Alessandro e Ludovico Urbani, Niccolò Alunno, Vittore Crivelli e il Pinturicchio, ed. Vittorio Sgarbi and Stefano Papetti, 39–52. Exh. cat. Milan: Federico Motta, 2001., 162–63, no. 22; and Romina Vitali, in Costanzi, Costanza, ed. Le Marche disperse: Repertorio di opere d’arte dalle Marche al mondo. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2005., 116, no. 37. ↩︎

-

Antonio Paolucci first proposed a date after 1490 (in Paolucci, Antonio. “Lorenzo di Alessandro da San Severino e alcune considerazioni sulla pittura marchigiana del tardo quattrocento.” Paragone 25, no. 291 (May 1974): 35–51., 43–44), which seems too late, while other scholars have opted for a very broad time frame in the last twenty years of the artist’s activity, between 1481 and around 1500. See Baker, Christopher, and Tom Henry. The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue. London: National Gallery, 1995., 390; Paciaroni, Raoul. Lorenzo d’Alessandro detto il Severinate: Memorie e documenti. Milan: Federico Motta, 2001., 106; and Federico Zeri, in Fototeca Zeri, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna, inv. no. 18139. There is no reason to assume, as is posited by Giampiero Donnini (in Donnini, Giampiero. “Lorenzo d’Alessandro da San Severino: La vocazione luministica e toscana di un pittore gotico alle soglie del Rinascimento.” In I pittori del Rinascimento a Sanseverino: Lorenzo d’Alessandro e Ludovico Urbani, Niccolò Alunno, Vittore Crivelli e il Pinturicchio, ed. Vittorio Sgarbi and Stefano Papetti, 39–52. Exh. cat. Milan: Federico Motta, 2001., 162), that the altarpiece must have been commissioned shortly after the Blessed Costanzo’s death. ↩︎

-

Mauro Minardi, in Costanzi, Costanza, ed. Le Marche disperse: Repertorio di opere d’arte dalle Marche al mondo. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2005., 192, no. 255, pl. 129. ↩︎

-

Gilbert, Creighton. “An Addition to Lorenzo d’Alessandro da Sanseverino.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin 40, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 20–25., 24–25. ↩︎

-

Paciaroni, Raoul. Lorenzo d’Alessandro detto il Severinate: Memorie e documenti. Milan: Federico Motta, 2001., 116. ↩︎

-

Maria Rosaria Valazzi, in Sgarbi, Vittorio, and Stefano Papetti, eds. I pittori del Rinascimento a Sanseverino: Lorenzo d’Alessandro e Ludovico Urbani, Niccolò Alunno, Vittore Crivelli e il Pinturicchio. Exh. cat. Milan: Federico Motta, 2001., 200; and Chui, Sue Ann. “Lorenzo d’Alessandro da Sanseverino’s Crucifixion; St. Michael: Art Historical Context and Technical Analysis of an Italian Fifteenth-Century Double-Sided Processional Standard.” Journal of the Walters Museum 63 (2005): 41–56., 47. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 37.496, https://art.thewalters.org/detail/40438/the-crucifixion-saint-michael/. See Paciaroni, Raoul. Lorenzo d’Alessandro detto il Severinate: Memorie e documenti. Milan: Federico Motta, 2001., 110–11; and Maria Rosaria Valazzi, in Sgarbi, Vittorio, and Stefano Papetti, eds. I pittori del Rinascimento a Sanseverino: Lorenzo d’Alessandro e Ludovico Urbani, Niccolò Alunno, Vittore Crivelli e il Pinturicchio. Exh. cat. Milan: Federico Motta, 2001., 148–51 (with previous bibliography). The Baltimore and Brooklyn standards were the subject of technical comparisons by Sue Ann Chui, in Chui, Sue Ann. “Lorenzo d’Alessandro da Sanseverino’s Crucifixion; St. Michael: Art Historical Context and Technical Analysis of an Italian Fifteenth-Century Double-Sided Processional Standard.” Journal of the Walters Museum 63 (2005): 41–56., 41–56. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 40328, https://catalogo.museivaticani

.va ; and inv. no. 113, respectively. ↩︎/index .php /Detail /objects /MV .40328 .0.0 -

Inv. no. 1654, https://barberinicorsini.org/artwork/?id=WE4364; and inv. no. 948, respectively. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. MO2003.10. On these works, see the recent compilation of Marchigian processional standards on panel in Schmidt, Victor M. Stendardi e gonfaloni processionali dalle Marche: Tardo Medioevo e Rinascimento. Macerata Feltria: Centro Studi G. Mazzini, 2020., 92–93, 95, 101–3, 117, nos. Ta10, Ta17/Ta18, Ta27 (with previous bibliography). Unlike most processional standards, the Bernardino di Mariotto example at Yale was not originally painted on both sides of a single panel (later sawn in half) but on two separate panels, each having the same thickness as Lorenzo’s Virgin and Child. These were mounted back-to-back around some kind of armature, no longer extant, presumably secured by their frame, to which the carrying pole was attached. Like Bernardino’s panels, the reverse of the present Virgin and Child shows no evidence of having been thinned nor of having been attached to any other wood surfaces, but its frame moldings along both vertical edges were clearly trimmed in depth. They could originally have extended back to enframe another panel of the same dimensions, oriented in the opposite direction. ↩︎

-

Paciaroni, Raoul. Lorenzo d’Alessandro detto il Severinate: Memorie e documenti. Milan: Federico Motta, 2001., 116. ↩︎