James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

The panel support, of a horizontal wood grain, has been reduced to a depth varying from 1.3 to 1.7 centimeters, cradled, and waxed. Like its companion panel (see Apollonio di Giovanni, The Shipwreck of Aeneas), a 1.5-centimeter-thick engaged frame molding along all four sides is original but has been regessoed and regilt. There is no visible seam joining planks in the support, but numerous diagonal splits are visible through the paint surface and have been repaired with old repaints. Unlike its companion panel, this painting was not cleaned in 1951 and is in remarkably good condition. Losses are confined to the usual percussion damages suffered by cassone panels in general. The gilt decoration is beautifully preserved.1

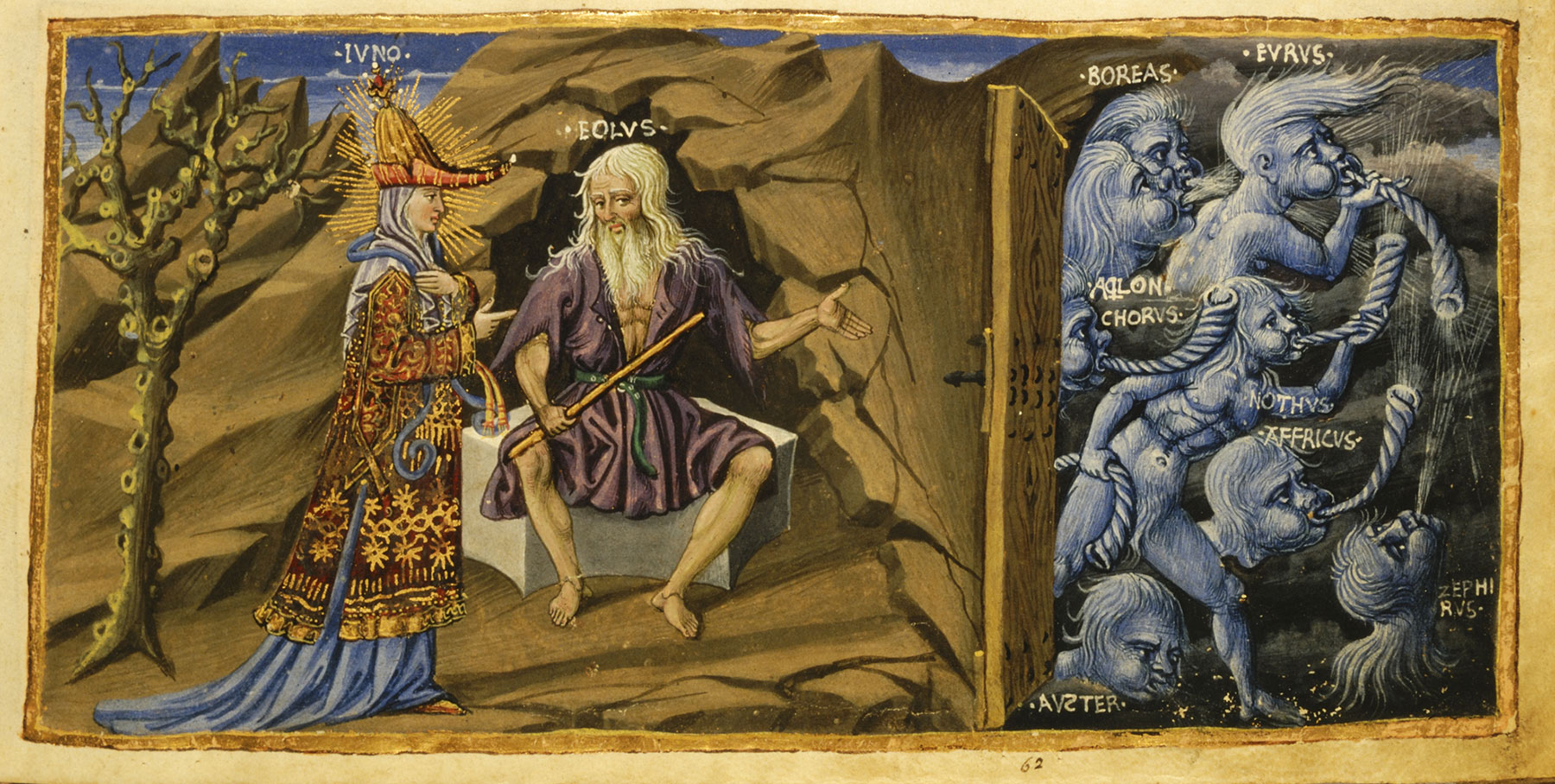

This panel and its pair (see Apollonio di Giovanni, The Shipwreck of Aeneas) represent a compendium of scenes drawn primarily from the first book of Virgil’s Aeneid. At the upper-left corner of the latter panel, Juno, wearing a gold hat and vest over a blue dress and identified by her name inscribed before her—“GVNONE”—descries the ships of Aeneas and his retainers escaping the sack of Troy (1:55–74). Immediately below, she approaches Aeolus, god of the winds, seated before his cave with the inscription “EVLO.” Juno begs him for a storm to destroy the Trojan fleet (1:95–109). Aeolus obeys his queen and releases the winds (1:117–30), symbolized by an army of blue giants blowing horns and brandishing swords alongside the rocky isle of his cave and by three disembodied blue heads with puffed cheeks and streaming hair. These are variously labeled “AESTALE,” “LIBECIO,” “TR[AMONTALE],” “GRECHO,” “SOLO.O,” “LEVANTE,” “MEZODI,” and “PONENTE,” all names of the winds. Completing the left half of the panel is the destruction wreaked by the winds upon the fleet (1:144–76): masts snapped, sails torn, men thrown overboard, ships foundering. To the right of center, Neptune, riding a chariot drawn by a pair of dolphins and accompanied by the inscription “NET/U[NO],” stills the winds (1:177–220), directly addressing two of them—the east wind and the west wind (1:186), here portrayed as blue heads labeled “EVRO” and “ZEFIRO,” facing him calmly and without puffed cheeks. Behind the chariot of Neptune, Aeneas and his companions, in the few boats that survived the tempest, come safely to harbor on the coast of North Africa, where they find a spring of fresh water surrounded by seats carved in the stone (1:221–37). Aeneas, wearing a golden robe and a gold hat with blue band, and Achates, wearing a rose-colored robe and gold hat, both identified by inscriptions with their names, set out to explore the coast and, at the far right of the composition, encounter Venus disguised as a huntress (1:441–73). In answer to his question, Venus tells Aeneas that he has landed in Libya, that the rest of his fleet is safe although scattered, and that he should follow the path to meet Queen Dido in Carthage, whose history she tells him (1:474–572). Only as she turns to leave, at the top right of the painting, does Aeneas recognize her as his mother, the goddess Venus, inscribed “VENERE” (1:573–80). Though these are seemingly minor episodes within the overall drama of the composition, the artist has taken some pains to follow Virgil’s descriptions closely, showing Venus clad in a short hunting dress, her knees bare, and holding a bow, while she speaks with Aeneas (1:451–55), but:

. . . when she turned,

her neck was glittering with a rose brightness;

her hair anointed with ambrosia,

her head gave all a fragrance of the gods;

her gown was long and to the ground; even

her walk was sign enough she was a goddess (1:573–78).2

The narrative continues in the present panel, but in less orderly fashion than it had in the first. At the left and occupying nearly a third of the composition is the hunt of Aeneas, an event that, in the poem, preceded Aeneas’s encounter with Venus. Having climbed a promontory to search for any sign of his other ships, Aeneas instead sees three stags leading a large herd through the valley. He shoots seven of these, one for each of his surviving crews, and brings them back to the encampment as food for his exhausted men (1:251–70). It was after this feast that Aeneas and Achates, exploring alone, met Venus in the woods and were urged by her to continue to Carthage. The goddess hid them within a dark cloud so that they were invisible on their arrival. Upon seeing Carthage, Aeneas marvels at the wealth and industry of the city as he watches its construction (1:601–20)—portrayed to the right of center in the Yale panel—and declaims, “How fortunate are those / whose walls already rise” (1:619–20), foreshadowing the eventual founding of Rome by his descendants. In the center of the panel is the temple of Juno at Carthage, decorated with scenes from the Trojan War (1:632–97). Aeneas and Achates enter, still hidden within the cloud, and watch as Queen Dido receives an embassy from the remainder of the Trojan fleet that had washed up elsewhere on the shores of Libya (1:720–32), symbolized by a small vignette at the left of center in the panel, below the scene of Aeneas’s hunt. The Trojans and their spokesman, Ilioneus, plead for shelter and for license to search for their lost commander, Aeneas (1:735–90). Dido graciously assents (1:791–815), and Aeneas, standing in the right bay of the temple, reveals himself when his mother dispels the cloud in which she had cloaked him (1:825–58).

At the far right of the panel is a visual coda inserted presumably as a gloss on Aeneas’s vision of the construction of Carthage. In Book 7 of the Aeneid, Aeneas and his chief captains, having finally arrived in Italy and disembarked on the shores of the Tiber, rest on the grass and feast on fruit heaped on platters made of wheat cakes, as they had been instructed by Jove (7:135–40). Still hungry after this repast, they devour the wheat cakes as well, prompting Ascanius, Aeneas’s son, to joke that “we have consumed our tables, after all” (7:147), fulfilling the prophecy of his grandfather Anchises that the time had come to found their city. Above the circle of Trojans seated on the lawn is another of the omens prophesied to foretell the location of the new city: “A huge white sow stretched out upon the ground together with a new-delivered litter of thirty suckling white pigs . . . that place will be the site set for your city” (3:508–11, 8:52–57). Above this is a full vision of Rome as it would look in the fifteenth century, including the Castel Sant’Angelo outside the city walls, the Pantheon, Trajan’s Column, and the Capitoline Hill.

Distinguished for their enviable state of preservation, for the quality of their execution, and for still being together as a pair, these two cassone panels have long been objects of special attention among historians for their detailed recapitulation of Virgil’s narrative poem. They were attributed to Paolo Uccello by James Jackson Jarves and Russell Sturgis, Jr.3 William Rankin was the first to group them together with two others in the Jarves collection—assigned by their owner variously to Piero della Francesca (Apollonio di Giovanni, The Meeting of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba) and Dello Delli (Apollonio di Giovanni, A Tournament in Piazza Santa Croce)—as the work of a single, unknown Florentine painter.4 Mary Logan Berenson agreed that these four paintings were by a single hand, whom she characterized as emerging from the workshop of Francesco Pesellino.5 She noted that the illuminations in a Virgil manuscript in the Biblioteca Riccardiana, Florence (fig. 1),6 are identical to these in conception and detail, and she grouped with them another pair of cassone fronts in Hannover, Germany (see Paolo Uccello, A Battle of Greeks and Amazons (Theseus and Hippolyta or Achilles and Penthesileia?); Allegories of Hope and Justice; Reclining Nude, fig. 6), the subjects of which she did not recognize. The connection to the Riccardiana Virgil was acknowledged by Osvald Sirèn, who did not venture to name the artist responsible.7 Paul Schubring used this group of works as the basis for coining the name “Dido Master,” having noted that the Hannover cassoni also recounted episodes from the story of Aeneas and Dido at Carthage.8 His further attributions to this Master, however, were somewhat erratic and based more on iconography than style. They were reviewed and rationalized by Richard Offner, who renamed the painter more expansively the “Virgil Master,” characterizing him as “the most fashionable and finished of all Florentine cassone-painters.”9 Offner also added several religious paintings to this workshop’s production, while Bernard Berenson enlarged the corpus of cassone panels further and renamed the artist the “Master of the Jarves Cassoni,” perhaps a tacit acknowledgment of Offner’s claim that the Yale panels “reveal him more adequately here than anywhere else.”10

Historical identification of this painter variously named the Dido Master, Virgil Master, or Master of the Jarves Cassoni occurred in 1944, when Wolfgang Stechow associated a cassone panel recently acquired for the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College in Ohio with an entry in the account book, covering the years 1446–63, from the Florentine workshop jointly operated by Marco del Buono and Apollonio di Giovanni.11 The Oberlin panel (fig. 2) represents a battle of Greeks and Persians and incorporates the arms of the Rucellai and Vettori families among its decorative details, permitting its identification with a commission recorded in the account book commemorating the marriage in 1463 of Pietro di Francesco Vettori and Caterina di Giovanni Rucellai.12 Stechow recognized that the Oberlin panel and a companion to it that had been destroyed during the German air bombardment of Bath, England, could both be attributed to the artist responsible for the Jarves Aeneid panels and the Riccardiana Virgil, establishing that painter’s identity as either Marco del Buono or Apollonio di Giovanni.

A key to resolving this last question was offered by Ernst Gombrich in 1955, when he published a Latin epigram of the Florentine poet Ugolino Verino (1438–1516), composed between 1458 and 1464, that included the lines:

Once Homer sang of the walls of Apollo’s Troy burned on Greek pyres, and again Virgil’s great work proclaimed the wiles of the Greeks and the ruins of Troy. But certainly the Tuscan Apelles Apollonius now painted burning Troy better for us. And also the flight of Aeneas and the wrath of iniquitous Juno, with the rafts tossed about, he painted with wondrous skill; no less the threats of Neptune, as he rides across the high seas and bridles and stills the swift winds. He painted how Aeneas, accompanied by his faithful Achates, enters Carthage in disguise; also his departure and the funeral of unhappy Dido are to be seen on the painted panel by the hand of Apollonius.13

Gombrich assumed that Verino was not directly describing the Yale cassone fronts—from which some scenes mentioned by the poet are omitted—but rather some large painted panel, possibly a spalliera panel, that resembled them. As hard evidence, therefore, the epigram is circumstantial rather than conclusive, but that Apollonio is to be credited as the head artist of the workshop does not seem to be contradicted by any other available information and has been universally adopted in all subsequent literature. At the same time, it might be wondered whether, in fact, Verino’s description could apply directly to the Yale panels. The missing scenes could have been portrayed on backboards or spalliere now lost but originally part of the chests of which the Yale panels decorated the fronts: on the first, above the panel depicting The Shipwreck of Aeneas, the burning of Troy and the flight of Aeneas with Ascanius, Anchises, and the household gods; on the second, above the present panel depicting Aeneas at Carthage, the departure of Aeneas and the death of Dido. It has always been assumed that Verino’s reference to “the painted panel by the hand of Apollonius” implies that all the scenes he mentions appeared together in a single continuous narrative. The text, however, if taken literally, only mentions the departure of Aeneas and funeral of Dido in “the painted panel.” It is certainly possible that the other scenes occurred on associated panels. Absent the evidence of Verino’s epigram, such a possibility would also explain the oddity of having omitted the climactic final scene from so detailed a narrative as is found on the Yale cassoni in favor of a tangentially related vision of the founding of Rome.14

Proposals for dating of the Yale panels, subsequent to their recognition as works by Apollonio di Giovanni, have invariably been based on assumptions regarding the date of the Riccardiana Virgil and Verino’s epigram. Schubring thought the Riccardiana manuscript had to have been completed by 1452 at the latest, as he felt that the scene it included of the building of Carthage recorded the unfinished state of the Palazzo Medici, then under construction in Florence.15 Gombrich debunked this idea and pointed out that the scribe of the manuscript as identified in its colophon, Niccolò d’Antonio de’ Ricci, was born in 1433, making it unlikely that he wrote this text before the late 1450s.16 A terminus ante quem for the manuscript is established by the death of Apollonio di Giovanni in 1465, and Gombrich thought that date might also be taken as a plausible terminus a quo, on the assumption that a possible explanation for the illuminations being left incomplete was interruption of their progress by the demise of the artist. For Gombrich, the Yale panels probably preceded the Riccardiana manuscript, as the latter “copied” the motif of the winds blowing to the right without the narrative justification of the episodic arrangement of scenes on the cassone front. Although discounted by Ellen Callmann,17 this observation is telling: while the two works are certainly close in date, it seems more likely that the cassone panels preceded rather than followed the manuscript. There is only one securely dated work by Apollonio di Giovanni known—the cassone front at Oberlin College (see fig. 2)—so firm comparatives for establishing a chronology on stylistic grounds do not exist. There is, however, no reason to believe categorically that the Yale cassone fronts cannot be late works by the artist, and dating them ca. 1460 is entirely reasonable in view of the scant circumstantial evidence available.

A potential anchor for dating the panels more precisely may be provided by two decorative devices, repeated in alternation and without variance, on the bulwarks of the galleys in the Shipwreck of Aeneas panel. These undoubtedly stand as references to coats of arms, one of which, nebuly argent and sable, could represent the Pitti family of Florence. Six marriages in the Pitti family are recorded in Apollonio di Giovanni’s account book: nos. 27 (“figliuola di Stoldo Rinieri, maritata a Salvestro di Ruberto Pitti”); 28 (“figliuola di Ruberto di Buonaccorso Pitti, maritata a Dante da Castiglione”) in 1446; 41 (“figliuola di Ruberto Pitti, maritata a Bernardo di Bernardo Ambruogi”); 55 (“figliuola di Giovanni di Iacopo de’ Pitti, maritata a Ruberto degli Albizzi”); 147 (“figliuola di Luca Pitti, a Francesco di Stefano Segni”); and 173 (“figliuola di Madonna Caterina da Rimini, a Giovanni di mess. Giovanni Pitti”).18 The second possible coat of arms on the Shipwreck of Aeneas panel, argent and azure, a scorpion gules, does not correspond to that of any of the families mentioned in the first five of this list of Pitti marriages. The last, no. 173, which is the final entry in the account book and therefore presumably datable 1463, is too imprecise to associate with a specific family or known coat of arms and is also for a smaller-than-usual fee. It is possible that Apollonio’s work continued past this date and, if the heraldry is reliable, that the Yale cassoni were executed between 1463 and the artist’s death in 1465, but that is purely speculative. —LK

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 49, nos. 57–58; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 50–51, nos. 43–44; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 18, nos. 43–44; Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 146; Logan, Mary. “Compagno del Pesellino et quelques peintures de l’école.” Gazette des beaux-arts, 3rd ser., 26 (1901): 18–34, 333–43., 335; Rankin, William. Notes on the Collections of Old Masters at Yale University, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Fogg Museum of Harvard University. Wellesley, Mass.: Department of Art, Wellesley College, 1905., 10, nos. 43–44; Rankin, William. “Cassone Fronts in American Collections.” Burlington Magazine 9, no. 40 (July 1906): 288. , 288; Rankin, William. “Cassone Fronts in American Collections—IV.” Burlington Magazine 11, no. 50 (May 1907): 128, 131–32., 131–32; Rankin, William. “Cassone Fronts in American Collections—V, Part I.” Burlington Magazine 11, no. 53 (August 1907): 338–41., 340; Rankin, William. “Cassone Fronts in American Collections—VI.” Burlington Magazine 12, no. 55 (October 1907): 62–64., 64; Rankin, William. “Cassone Fronts and Salvers in American Collections, VII.” Burlington Magazine 13, no. 66 (September 1908): 377, 380–82. , 382; Schiaparelli, Attilio. La casa fiorentina e i suoi arredi nei secoli XIV e XV. Vol 1. Florence: Sansoni, 1908., 284; Hülsen, Christian. “Di alcune vedute prospettiche di Roma.” Bulletino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma 39 (1911): 3–22., 4–10, 13–17, 19; Bombe, Walter. “Der Palazzo Medici-Riccardi und seine Wiederherstellung.” Monatshefte für Kunstwissenschaft 5 (1912): 216–23., 217; Hülsen, Christian. “On Some Florentine ‘Cassoni’ Illustrating Ancient Roman Legends.” Journal of the British and American Archaeological Society of Rome 4, no. 5 (1912): 466–78., 468–72, 475–76; Mather, Frank Jewett, Jr. “The Jarves Collection.” Yale Alumni Weekly 23, no. 36 (1914): 965–70., 968; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 87–89, nos. 34–35; Schubring, Paul. Cassoni: Truhen und Truhenbilder der italienischen Frührenaissance; Ein Beitrag zur Profanmalerei im Quattrocento. 2nd rev. ed. Leipzig, Germany: Karl W. Hiersemann, 1923. , 31–32, 85, 113, 254, 274, nos. 223–24, pl. 48; Schubring, Paul. “Cassone Pictures in America: Part One.” Art in America and Elsewhere 11, no. 5 (August 1923): 231–42., 241–42; D’Ancona, Paolo. “Virgilio e le arti rappresentative.” Emporium 65 (1927): 245–62., 258, 261–62 (1871.34 only); Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 6, 27–30, figs. 17–20; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 10. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1928., 548–54; Salmi, Mario. Review of Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions, by Richard Offner. Rivista d’arte 11 (1929): 267–73., 272; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 347; “Pagan Imagery in Renaissance Art: An Exhibition and Five Lectures.” Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 11, no. 1 (February 1942): 1–3. , 1–2; Stechow, Wolfgang. “Marco del Buono and Apollonio di Giovanni: Cassone Painter.” Bulletin of the Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College 1, no. 1 (June 1944): 5–21., 14–17; “Picture Book Number One: Italian Painting.” Special issue, Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 15, nos. 1–3 (October 1946): n.p., fig. 13 (1871.34 only); “Meister der Dido-Truhe.” In Allgemeines Lexikon der Bildenden Künstler, ed. Ulrich Thieme, Felix Becker, and Hans Vollmer. Leipzig, Germany: E. A. Seemann, 1950., 79; Rediscovered Italian Paintings. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1952., 32–33 (1871.34 only); Vagaggini, Sandra. La miniature florentine aux XIVe et XVe siècles. Milan: Electa, 1952., 14; Gombrich, Ernst H. “Apollonio di Giovanni: A Florentine Cassone Workshop Seen through the Eyes of a Humanist Poet.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 18, nos. 1–2 (1955): 16–34., 17–19, 23–24; D’Ancona, Mirella Levi. Miniatura e miniatori a Firenze dal XIV al XVI secolo: Documenti per la storia della miniatura. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1962., 23–25; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:18; *Robinson, Frederick B. “A Mid-Fifteenth Century Cassone Panel.” Museum of Fine Arts Bulletin, Springfield, Massachusetts 29, no. 3 (February–March 1963): n.p., n.p.; Scherer, Margaret R. The Legends of Troy in Art and Literature. New York: Phaidon, 1964., 185–86, 212, 241; Stechow, Wolfgang. Catalogue of European and American Paintings and Sculpture in the Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College. Oberlin, Ohio: Oberlin College, 1967., 8; Degenhart, Bernhard, and Annegrit Schmitt. Corpus der italienischen Zeichnungen, 1300–1450. Pt. 1, vol. 2. Berlin: Mann, 1968., 564; Virgil. Opera: Bucolica, Georgica, Aeneis; Manoscritto 492 della Biblioteca Riccardiana di Firenze. Ed. Berta Maracchi-Bigiarelli. Florence: Mycron 1969., 15–18; Callmann, Ellen. “Apollonio di Giovanni.” Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1970., 1–2, 4–5, 9–10, 13–14, 21, 23, 25–26, 37–40, 44–46, 79–80, 82–84, 97, 107, 115–16, 189–91; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 119–23, nos. 81–82; Watson, Paul F. “Virtu and Voluptas in Cassone Painting.” Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1970., 1, 225–26, 238; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 599; Wendy Gifford, in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 19, no. 10; Callmann, Ellen. Apollonio di Giovanni. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974., 1–3, 7, 11, 19–20, 22–23, 33, 41, 47–48, 54–55, 62, 68; Krautheimer, Richard. Rome: Profile of a City, 312–1308. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1980., 288, fig. 223 (1871.35 only); Baudille, Rita Parma. “L’Eneide e i cassoni.” In Virgilio nell’arte e nella cultura europea, ed. Marcello Fagiolo, 224–26. Exh. cat. Rome: De Luca, 1981., 224–26; Forte, Bettie. “Vergil’s Aeneid in Literature and Art of the Italian Renaissance.” Vergilius 28 (1982): 4–14., 4–5; Guidoni, Enrico. “Roma e l’urbanistica del trecento.” In Storia dell’arte italiana, vol. 2, Dal Medioevo al novecento, pt. 1, Dal Medioevo al quattrocento, 307–83. Turin: Giulio Einaudi, 1983., 364, fig. 275 (1871.35 only); Schiaparelli, Attilio. La casa fiorentina e i suoi arredi nei secoli XIV e XV. Vol. 2. Ed. Maria Sframelo, Laura Pagnotta, and Mina Gregori. Florence: Le Lettere, 1983., 81n233; Callmann. Ellen. “Apollonio di Giovanni.” In Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon. Munich: K. G. Saur, 1992., 525; Kenney, Elise K., ed. Handbook of the Collections: Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1992., 135; Morrison, Jennifer Klein. “Apollonio di Giovanni’s Aeneid Cassoni and the Virgil Commentators.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin (1992): 27–47., 34–35; Callmann, Ellen. “Apollonio di Giovanni.” In The Dictionary of Art. New York: Macmillan, 1996., 228; Brancia di Apricena, Marianna. Il complesso dell’Ara Coeli sul Colle Capitolino (IX–XIX secolo). Rome: Quasar, 2000., 116 (1871.35 only); Bollati, Milvia. “Apollonio di Giovanni di Tommaso.” In Dizionario biografico dei miniatori italiani: Secoli IX–XVI, ed. Milvia Bollati, 44. Milan: Sylvestre Bonnard, 2004., 44 (1871.34 only); Miziołek, Jerzy. “The ‘Odyssey’ Cassone Panels from the Lanckoroński Collection: On the Origins of Depicting Homer’s Epic in the Art of the Italian Renaissance.” Artibus et historiae 27, no. 53 (2006): 57–88., 60; Francesca Pasut, in Boskovits, Miklós, ed. Italian Paintings from the 13th to the 15th Century. The Alana Collection 1. Florence: Polistampa, 2009., 35nn3, 10 (1871.35 only); Chong, Alan. “The American Discovery of Cassone Painting.” In The Triumph of Marriage: Painted Cassoni of the Renaissance, ed. Cristelle Baskins, 66–91. Exh. cat. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2009., 72, fig. 44 (1871.34 only); Alessio Formolo, in De Marchi, Andrea, and Lorenzo Sbaraglio, eds. Le opera e i giorni: Exempla virtutis, favole antiche e vita quotidiana nel racconto dei cassoni rinascimentali. Florence: Masso delle Fate, 2015., 131 (1871.34 only)

Notes

-

Contrary to the fears expressed by Charles Seymour, Jr., the condition of this panel is not “probably worse than its companion.” Its surface is not “extensively repainted,” and the “gilt of the ‘pictures’ represented in the central temple” is not “completely renewed.” See Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 123. ↩︎

-

Translations throughout by Allen Mandelbaum, in Virgil. The Aeneid of Virgil. Trans. Allen Mandelbaum. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971.. ↩︎

-

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 49; and Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 50–51. ↩︎

-

Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 146. ↩︎

-

Logan, Mary. “Compagno del Pesellino et quelques peintures de l’école.” Gazette des beaux-arts, 3rd ser., 26 (1901): 18–34, 333–43., 335. ↩︎

-

Misindentified by Logan as Biblioteca Magliabecchiana, Florence. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 87–88. ↩︎

-

Schubring, Paul. Cassoni: Truhen und Truhenbilder der italienischen Frührenaissance; Ein Beitrag zur Profanmalerei im Quattrocento. 2nd rev. ed. Leipzig, Germany: Karl W. Hiersemann, 1923. , 31–32, 85, 113, 254; and Schubring, Paul. “Cassone Pictures in America: Part One.” Art in America and Elsewhere 11, no. 5 (August 1923): 231–42., 241–42. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 6, 27–30. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 347, quoting Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 6. Berenson ignored Offner’s attributions to this painter of any religious images, one of which was in his own collection and which he persisted in believing was by a follower of Pesellino. ↩︎

-

Stechow, Wolfgang. “Marco del Buono and Apollonio di Giovanni: Cassone Painter.” Bulletin of the Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College 1, no. 1 (June 1944): 5–21., 4–23. The account book (Biblioteca Nazionale, Florence, MS Magliabechiano 37, cod. 305) had been discovered by Heinrich Brockhaus, who called it to the attention of Aby Warburg. Warburg made a copy of the text, which he provided to Schubring for publication; Schubring, Paul. Cassoni: Truhen und Truhenbilder der italienischen Frührenaissance. Leipzig, Germany: K. W. Hiersemann, 1915., 420–37. An emended version of the text is included in Callmann, Ellen. Apollonio di Giovanni. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974., 76–81. ↩︎

-

The connection of the cassone panel to the document had been noted by Schubring, who, however, knew the cassone only from its description in the catalogue of the Toscanelli sale (Sambon’s, Florence, April 9–23, 1883) and could not, therefore, judge its style; see Schubring, Paul. Cassoni: Truhen und Truhenbilder der italienischen Frührenaissance. Leipzig, Germany: K. W. Hiersemann, 1915., 111. ↩︎

-

Gombrich, Ernst H. “Apollonio di Giovanni: A Florentine Cassone Workshop Seen through the Eyes of a Humanist Poet.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 18, nos. 1–2 (1955): 16–34., 17. ↩︎

-

Ellen Callmann presented documentary evidence that Apollonio painted spalliera backboards for cassoni at least as early as 1459 and that these became increasingly fashionable in the 1460s and 1470s; see Callmann, Ellen. “Apollonio di Giovanni and Painting for the Early Renaissance Room.” Antichità viva 27, nos. 3–4 (1988): 5–18., 5–18. ↩︎

-

Schubring, Paul. Cassoni: Truhen und Truhenbilder der italienischen Frührenaissance. Leipzig, Germany: K. W. Hiersemann, 1915., 430–37. ↩︎

-

Gombrich, Ernst H. “Apollonio di Giovanni: A Florentine Cassone Workshop Seen through the Eyes of a Humanist Poet.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 18, nos. 1–2 (1955): 16–34., 19. ↩︎

-

Callmann, Ellen. Apollonio di Giovanni. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974., 11. ↩︎

-

Callmann, Ellen. Apollonio di Giovanni. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974., 77–81. ↩︎