Sale, Christie’s, Milan, November 25, 2011, lot 23; Richard L. Feigen (1930–2021), New York, 2011

The panel support, of a horizontal wood grain and 3.5 centimeters thick, comprises two planks of poplar with a seam rising on a slight diagonal from right to left, beginning 26 centimeters from the top at the right edge and ending 24 centimeters from the top at the left edge. The seam is very slightly open at either end of the panel. The right edge of the panel also shows two partial splits, 8.5 and 34.1 centimeters from the top. All of these have resulted in minimal paint loss. A 7.5-centimeter-wide cutout for a lock mechanism has been excavated in the depth of the panel at the center of the top edge, and a keyhole is visible, cut through the panel surface, 61.5 centimeters from the right edge. A barb along all four edges of the paint surface and exposed wood outside of the barb indicate the removal of engaged frame moldings, while mitered incisions at each corner from the original fitting of these moldings suggest that the panel in its present format is complete, unless it were missing lateral extensions that may have contained coats of arms. The painting and gilt surfaces show wear typical of cassone panels, with overall abrasion and scattered local losses due to percussion damage, clustered more densely within a 30-centimeter radius of the keyhole. The sky is particularly difficult to read because of flat, discolored retouches and exposed gesso, confusing the transitions from light blue near the horizon to deeper blue at the top. All the silver decoration of the armor and horse trappings has been repainted with a thick emulsion of silver pigment, with the exception of a single helmet at the right edge of the composition, which reveals the degree of wear to which all the silver must have been subjected but also the subtlety of form it still revealed before overpainting.

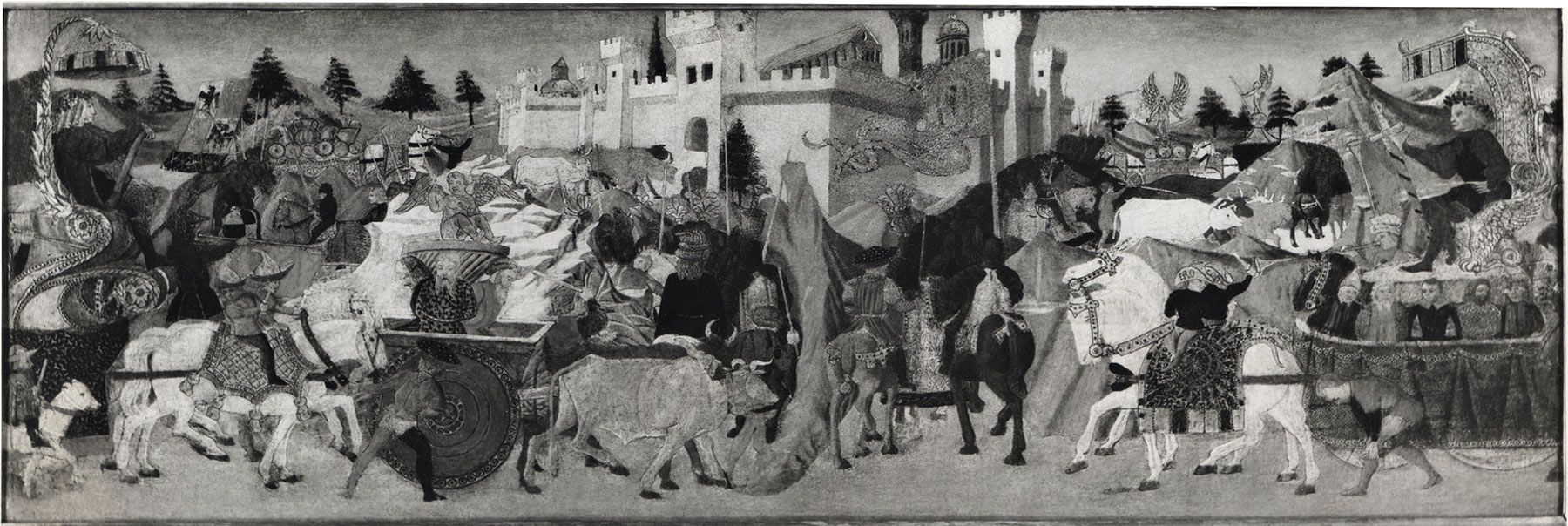

While portrayals of classical Roman military triumphs are not uncommon on painted cassoni in the fifteenth century, this cassone front is unusual in representing two separate processions in a single scene. At the left, a youthful general with long blond hair, wearing a full suit of (silver) armor and resting his hand on a baton of authority, is enthroned beneath a canopy atop a cart processing to the right. The cart is drawn by two white horses ridden by pages with the word “ROMA” embroidered in pearls on the brims of their hats. In front of the general’s cart, two oxen are yoked to a wagon bearing three elderly bearded prisoners and a gilded statue of a young, winged god resembling Eros; lettering around the base of the statue is now illegible. The oxen are preceded by a cavalcade of mounted knights who, having reached a rocky outcrop in the center of the panel, turn backward into depth, following a path that winds among the hills. Further along this path are glimpses of infantry, more treasure-laden carts, pairs of oxen, and mounted knights entering the gate of a walled city—presumably Rome—at the top center of the panel. On the right is a similar procession directed to the left, toward the center of the panel, featuring another general in full armor enthroned beneath a canopy, displaying his sword rather than a baton. A line of captives ranging in age and possibly of both sexes encircles the foot of the throne. A knight in the cavalcade leading the cart holds a large banner with a red circle on a dark blue field but with no legible device in the circle. This procession, too, winds back through the landscape toward the same walled city in the distance.

Paul Schubring recorded two other cassone fronts that portray a double triumph like this one, identifying both as representing the entry of the emperor Vespasian and his sons, Titus and Domitian, into Rome in A.D. 71, following the sack of Jerusalem by Titus the previous year.1 Flavius Josephus and Dio Cassius recount that the Roman Senate, exceptionally, declared the double triumph, recognizing that Vespasian began the suppression of the Judean revolt under the emperor Nero and Titus completed it during his father’s reign. If the Yale panel is the Triumph of Titus and Vespasian, it is difficult to know which armored general is meant to be Vespasian and which Titus—who succeeded Vespasian as emperor in A.D. 79—unless they are instead meant to represent Titus and his brother, Domitian, who, in turn, succeeded Titus as emperor in A.D. 81. Either way, literal adherence to Josephus’s description of the triumph was not the artist’s concern, as none of the spoils of war refer specifically to the Temple of Jerusalem or any of the treasures depicted on the Arch of Titus in Rome, dedicated by Domitian in A.D. 81. to memorialize his brother’s achievement and consolidate his own claim to authority.

The Yale panel also stands apart from other images of military triumphs on cassone fronts in that at least one complete and two partial replicas of it are known, all originating from different artist’s studios. The complete replica, attributable to the workshop of Apollonio di Giovanni and Marco del Buono, was formerly in the collection of Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn (fig. 1).2 Measuring 40.7 by 120 centimeters, this panel accurately copies nearly every detail of the composition of the Yale panel. It differs only in simplifying the elegant draftsmanship and coloration of the original, suppressing the spatial function of landscape details, and altering the profile of buildings rising above the battlemented walls of the city in the background (specifically, in the area directly below the keyhole in the front of the original chest). So exact is the copy that it is necessary to assume that the artist of the Williams-Wynn panel had direct access to the Yale panel, either in the home of its original owner or as a member of the workshop in which it was painted. The partial replicas both occur on cassone fronts attributable to Giovanni di Ser Giovanni, called Lo Scheggia: one formerly in the collection of Franklin Mott Gunther and Louisa Facasanu, in Washington, D.C. (fig. 2),3 the other in the Musée National de la Renaissance in Écouen, France (which copies the double triumph motif, as Schubring had noted).4 In the former, the vignette of the right-hand triumphal cart with sword-bearing general and a ring of bound captives, the two white horses pulling it and their riders turning backward, and the soldier/attendant bending over to adjust his leggings in front of the cart are reproduced—in reverse and at the left of the adapted composition. The dwarf(?) riding an exotic if difficult to identify animal cropped at the left edge of the Yale panel reappears in the former Gunther-Facasanu panel as well, transposed to the center of the procession. Here, the borrowings are sufficiently generic to suggest that the artist could have been working with a drawing for or after the original, rather than relying on direct access to the painted source, and yet they are specific enough to leave no doubt that they rely directly on this prototype. The same drawing could have been used to create the Écouen cassone front, in which both carts and their horses, again reversed, are adapted, as is the detail of a page bending to fasten his leggings. This figure is otherwise an inexplicable addition to the narrative.5

The attribution of the Yale panel to Paolo Uccello was made by the present author (verbally) at the time of its sale in 2011 and confirmed by Everett Fahy.6 Although recent scholarship has acknowledged oblique documentation that Paolo Uccello was involved in painting cassone fronts, it has been reluctant to admit any such painted panels to his accepted oeuvre.7 This reticence is unnecessary. Six surviving cassoni, possibly seven, not only reflect motifs and compositional conceits deriving from Uccello’s better-known monumental works but also are painted with a level of technical skill and conceptual sophistication that is typical of his works alone among all fifteenth-century Florentine painters. The six cassoni that may be attributed without hesitation to Uccello are:

-

The Battle of Aeneas and Turnus at Latium, Seattle Art Museum (see Paolo Uccello, A Battle of Greeks and Amazons; Allegories of Hope and Justice; Reclining Nude, fig. 6);

-

The Story of Camilla, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Tours, France (see Uccello, Battle of Greeks and Amazons, fig. 7);

-

The Battle of Metaurus, private collection, England (see Uccello, Battle of Greeks and Amazons, fig. 8);

-

The Banquet of Aeneas and Dido, Landesmuseum, Hannover, Germany (see Uccello, Battle of Greeks and Amazons, fig. 10);

-

A Battle of Greeks and Amazons (Theseus and Hippolyta or Achilles and Penthesileia?);

-

the present panel.

The first five of these are late works by Paolo Uccello, painted after 1460. A seventh panel, representing the first episodes in the story of Susannah and the Elders, in the Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon, France, is earlier than all but the present panel. Its attribution, however, is vigorously contested.8

Among the bases for attributing the present panel to Paolo Uccello may be listed the free invention of the canopies adorning the two triumphal carts and the perfect radial foreshortening of their structures and of the plumes in helmets among the accompanying cavalry. Although similar devices appear in cassoni from other workshops, none reaches the level of geometric creativity and precision evident here. This is true as well of the sophisticated rendering of the battlemented city walls and towers and of the floriated decoration on the edges of the pyramid within the city; an identical form appears also in the background of Uccello’s frescoes in the Cappella dell’Assunta in Prato (ca. 1433–34). The turn of horses and oxen backward into space and the particular tonal gradations of the palette with which they are rendered, relying on the juxtaposition of contrasting planes of light and dark colors, are reminiscent of the Sir John Hawkwood monument (1436) in Florence Cathedral or the San Romano battle scenes.9 Other oddities frequently encountered in Uccello’s work and rarely found elsewhere are the solecisms of horses with both near legs raised simultaneously—an idiosyncrasy for which the artist was criticized by Giorgio Vasari10 but which must have been deliberate and was, in all likelihood, tongue in cheek. The peculiar animal ridden by a small figure at the left edge of the composition is an exact duplicate of one of the beasts at the top of the throng in the fresco of the Creation in the Chiostro Verde at Santa Maria Novella, Florence (fig. 3), and the facial types of the captives in both carts recur in numerous early works by Uccello, notably in the Quarate predella of ca. 1435.11 Such features argue not only for an attribution to Uccello but also for a date within the decade of the 1430s, close to the beginning of the artist’s career but, perhaps more significantly, at the start of the tradition of painting scenes from Roman history on wedding cassoni. It is quite possible that this panel represents a prototype for a fashion in domestic decoration that endured in Florence nearly to the end of the fifteenth century. —LK

Published References

Unpublished

Notes

-

Baron Lazzaroni, Paris, and Musée de Cluny, Paris, now Musée National de la Renaissance, Écouen, no. E. Cl. 7509, as The Reconciliation of Romulus and Titus; see Schubring, Paul. Cassoni: Truhen und Truhenbilder der italienischen Frührenaissance. Leipzig, Germany: K. W. Hiersemann, 1915., no. 122, pl. 22, and no. 128, pl. 25, respectively. The Écouen panel converts the subject from a triumphal entry to the reconciliation by suppressing all military emblems, including weapons and carts of prisoners. ↩︎

-

Sale, Sotheby’s, London, June 30, 1965, lot 14. This provenance stems from the record in the Fototeca Zeri, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna, inv. no. 13818. It is unclear whether the reference is to Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn (1891–1949), 8th Baronet; Sir Robert William Herbert Watkin Williams-Wynn (1862–1951), 9th Baronet; or Sir Owen Watkin Williams-Wynn (1904–1988), 10th Baronet. ↩︎

-

Sale, Sotheby’s, New York, June 12, 1975, lot 95; recorded in the Fototeca Zeri, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna (inv. no. 13804) as subsequently in a private collection in Geneva. See Bellosi, Luciano, and Margaret Haines. Lo Scheggia. Florence: Maschietto e Musolino, 1999., 97, recording an attribution by Everett Fahy. ↩︎

-

See note 1, above. ↩︎

-

Several opinions attempting to justify the inclusion of this figure are reported by Karinne Simonneau, in Alain Erlande-Brandenburg, Karinne Simonneau, and Christine Benoît. Les cassoni peints du Musée National de la Renaissance. Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 2004, 46–49, no. 6. None of these account for its being a direct copy of the Yale panel, which was not known at the time. ↩︎

-

Everett Fahy, letter, November 1, 2014, curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

See, for example, Minardi, Mauro. Paolo Uccello. Milan: Prima, 2017., 305, 345–46, 348n69, 349nn150–52. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. M. I. 533. This panel was attributed by the present author to Uccello and separated from its presumptive companion at the Musée du Petit Palais, inv. no. M. I. 534, representing the concluding episodes of the story of Susannah and the Elders and painted by Domenico di Michelino; Kanter, Laurence. “The ‘cose piccole’ di Paolo Uccello.” Apollo Magazine 152, no. 462 (August 2000): 11–20., 15–16. The attribution to Uccello was accepted by Miklós Boskovits but changed by Fahy to Zanobi Strozzi (both opinions are recorded in Laclotte, Michel, and Esther Moench. Peinture italienne: Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2005., 192) and by Andrea Staderini to an unknown follower of Fra Angelico (Staderini, Andrea. “Il confronto con le novità rinascimentali: Pittori di cassoni nella Firenze di metà quattrocento.” In Virtù d’amore: Pittura nuziale nel quattrocento fiorentino, 115–25. Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2010., 118, 121, fig 4). ↩︎

-

National Gallery, London, inv. no. NG583, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/paolo-uccello-the-battle-of-san-romano; Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence, inv. no. 1890 n. 479, https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/battle-of-san-romano; and the Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. no. MI 469, https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010065339. ↩︎

-

Vasari, Giorgio. Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori. With new annotations and comments by Gaetano Milanesi. 9 vols. Florence: G. C. Sansoni, 1878–85., 2:212: “Se Paolo non avesse fatto che quel cavallo muove le gambe da una banda sola, il che naturalmente i cavalli non fanno, perchè cascherebbono . . . sarebbe questa opera perfettissima” (And if Paolo had not made that horse move its legs on one side only, which naturally horses do not do, or they would fall . . . this work would be absolutely perfect). Translation from Vasari, Giorgio. Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects by Giorgio Vasari. 10 vols. Trans. Gaston du C. De Vere. London: Macmillan, 1912–14., 2:137. ↩︎

-

Museo Diocesano di Santo Stefano al Ponte, Florence. ↩︎