Cornelia, countess of Craven (1877–1961), Coombe Abbey, near Coventry, Warwickshire, England; Stora, Paris, by 1929; Marie Sterner Galleries, New York

The front and sides of the chest are each composed of two horizontal planks of poplar, 3.8 centimeters thick, to which are nailed and glued 1-centimeter-thick moldings framing the painted centers. The corner joins of the chest are original and undisturbed, but the corner pilasters applied to the front, the scale-decorated base molding, and the entablature molding on all sides are modern, probably nineteenth- or early twentieth-century repairs. Two large splits are visible in the lower plank of the front panel, passing from the left edge through the large ship at anchor and from the right edge through the small group of figures fighting before the walls of the city. The left end panel has four splits visible through the paint surface, while three partial splits in the right end panel have not disrupted the paint surface. The framing moldings on all three sides were regilded over original gilt surfaces in an early restoration, and the hinges of the lid—which is original to the chest (see fig. 3)—were replaced with modern hinges.

Cleaning of the chest by Sydney Nikolaus in 2016–18 removed severely discolored layers of varnish as well as oil-paint reinforcements over nearly all the silver-leaf armor and much of the landscape in the front panel, revealing extensive abrasion but few areas of major loss, other than the usual pattern of nicks and dents encountered in cassone panels. Abrasion is less pronounced in the end panels, both of which have more numerous flaking losses associated with movement of the wooden support. The interior of the lid had been cleaned separately from the rest of the chest by Nancy Krieg in 1984, when it was believed not to be integral to the original structure. Cleaning revealed overall abrasion and minor local losses but also that the upper half of the “sky” background on which the nude reclines is gesso preparation only: all pigment is missing from this area. Inpainting for loss compensation on all four panels is minimal and intended to enhance the legibility of forms without masking original materials.

This chest, discussed with some frequency in modern contextual literature but less well known in specialized art-historical studies, was acquired for the Yale University Art Gallery in 1933 through the agency of Maitland Griggs. Writing shortly afterward, the museum’s director, Theodore Sizer, explained:

There are five typical examples of Florentine quattrocento cassone painting in the Jarves Collection. Unfortunately all of these panels were taken from the chests and inappropriately framed before this collection came to Yale sixty-six years ago. Although they can be advantageously studied as polite examples of easel painting—which they are not—their original function and their proper relation to the chests they once so appropriately and delightfully adorned cannot be demonstrated.

It was with this in mind that the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale acquired a typical mid-fifteenth century Florentine cassone with elaborately painted panels in situ.

That the primary, if not exclusive, value of the chest to the collection was as an illustration of context—a pedagogical prop—was made clear in Sizer’s concluding remarks:

The name of the spirited Florentine painter of this chest is unknown. In this connection it is interesting to note that a pair of panels in the Jarves Collection, catalogued by the art critic, James Jackson Jarves, as the work of Paolo Uccello, changed by Osvald Sirén to a “Florentine Painter of about 1450,” and labelled in the Gallery as the “Virgil Master,” are now referred to by Bernhard Berenson in his Italian Pictures of the Renaissance as by the “Master of the Jarves Cassone.” Possibly this recent gift of the Associates may some day receive an equally interesting attribution.1

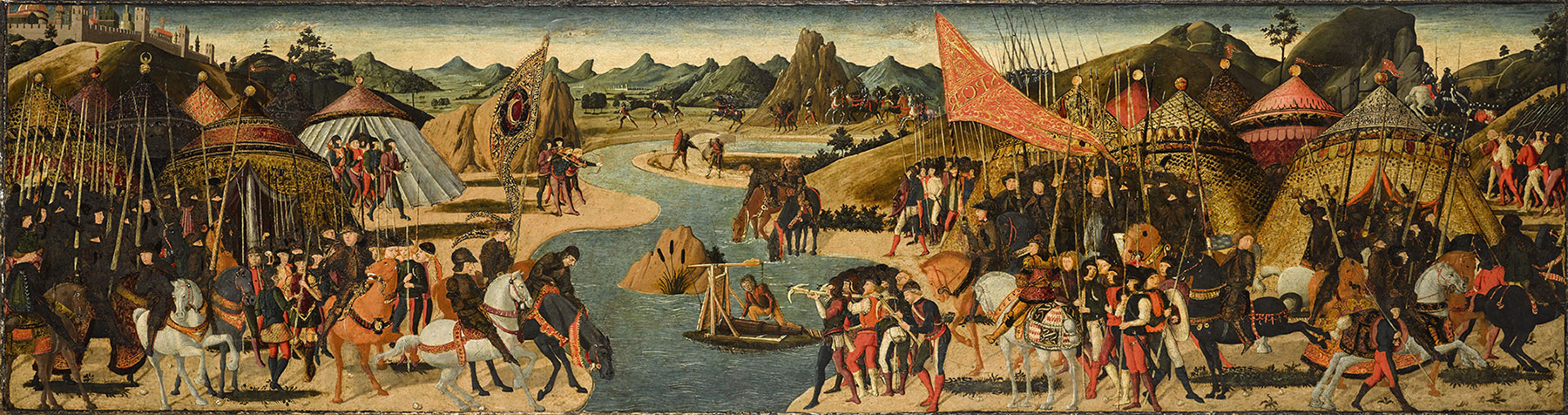

Previously, the chest had attracted no scholarly attention other than a brief mention by Tancred Borenius, who did not offer an attribution for it.2 He suggested that the subject of its main panel (fig. 1) might be the battle of Heraclius and Chosroes, comparing it to one of a pair of panels formerly in the Georges Chalandon collection, Lyon, France (fig. 2), thought to portray that subject, and he remarked on the exceptional rarity of its painted lid (fig. 3).3 Charles Seymour, Jr., repeated the scant information presented by Borenius, while Ellen Callmann observed only that the outside of the lid is one of only four extant examples to retain a painted textile decoration on its uppermost portion.4 She believed, however, that the lid was too small for the body of the chest and did not belong to it.

In her 1995 article on subjects from Boccaccio in Florentine cassone painting, Callmann amplified her belief that the Yale chest was reconstructed and partially modern.5 Calling it simply “Florentine, 1460s,” she accepted Paul Watson’s identification of the subject of the painted front of the chest—followed also by Vittore Branca, Cristelle Baskins, and Susan Wegner—as the battle of Theseus with the Amazon queen Hippolyta, taken from Boccaccio’s Teseida, Book 1.6 According to Callmann,

The moment here depicted is when the Greeks, having won a toehold on the shore, besiege the Amazon capital. The central emphasis is on two mounted protagonists who are in direct confrontation and are possibly meant to be Theseus and Queen Hippolyta. No such encounter, however, is described by Boccaccio who relates only that Theseus fights and kills many Amazons (1.73–78).7

Callmann supported this identification by referring again to the ex-Chalandon panel mentioned by Borenius, now in the Indianapolis Museum of Art (see fig. 2). This panel clearly does represent the battle described by Boccaccio in the Teseida, with the Amazons pouring in overwhelming numbers from the walls of their city in Scythia and the Greeks constrained to fight from their ships. Gaudenz Freuler mistakenly identified the Indianapolis cassone as the battle of Greeks and Amazons before the walls of Troy, when Achilles defeated the Amazon queen Penthesileia, on the grounds of having identified its pendant from the Chalandon collection as another Trojan War scene: the rape of Helen.8 Callmann, with greater probability, identified the subject of the second Chalandon panel not as relating to the Trojan War but as the meeting of Theseus and Hippolyta, an interpretation confirmed by Margaret Franklin.9

While there can be no doubt that the subject of the Yale cassone is a battle between Greeks and Amazons—the mounted warriors issuing from the city at the right wear long dresses over their armor and wield bows rather than swords or lances—there are several difficulties with interpreting the scene as the confrontation between Theseus and Hippolyta. According to Boccaccio, the Greeks were overwhelmed by the Amazons and forced to fight from their ships, many of which were burned or sunk before Theseus rallied his warriors. In the cassone, the Greek army has established an encampment (visible in the background at the left) and fights with cavalry directly in front of the walls of the city. The queen of the Amazons, furthermore, is probably to be identified as the figure in a gold dress on a white horse leading the charge of her armies in the center foreground, directly below the keyhole of the chest. She confronts a knight in black (formerly silver) armor, who sits astride a rearing white horse and threatens her with a sword. The same figure in a gold dress, now carrying a bow, is seen again at the lower right of the scene, being driven back toward the city gates in retreat, with a handful of her companions. Four knights threaten this group, the foremost of whom, brandishing a sword, is not the same warrior who faced the queen on horseback. It is possible that this is Achilles, not Theseus, and the battle is in defense of Troy rather than the Amazon capital. After the death of Hector, the armies of Queen Penthesileia rode to the defense of the Trojans and pushed the Greek armies back nearly to their ships. Achilles’s late arrival to the battle turned the tide, forcing the Amazons back to Troy, where he killed Penthesileia. The Amazon queen turning back to stand against the young knight at the right of the cassone may represent the unfolding of that final contest.10 Franklin disputes this interpretation, noting both that Penthesileia’s was only one of several armies fighting in defense of Troy and that, in the Teseida, Theseus ultimately forced the Amazons to retreat within the walls of their city.11 Either interpretation requires the artist to have overlooked or downplayed salient details of the original texts, which is far from implausible for a fifteenth-century cassone painter.

Allegorical figures are not commonly encountered on the end panels of Renaissance cassoni: Baskins cites examples in the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, in addition to the present chest.12 On the right end panel of the Yale cassone (fig. 4), Justice follows the form in which she was conceived by Piero del Pollaiuolo among the enthroned Virtues painted for the Mercanzia in Florence nearly contemporary to this chest, or in the slightly earlier relief by Luca della Robbia mounted in the ceiling of the chapel of the cardinal of Portugal in the church of San Miniato al Monte. She holds in her right hand a sword, emblem of her authority or power, and in her left a globe of the Earth, emblematic of the extent of her dominion, rather than the more usual symbol of a pair of scales. The figure seated in profile with her hands clasped before her in the left end panel (fig. 5) was identified by Borenius, followed by Sizer and all later writers, as Faith, presumably an extrapolation from her apparent attitude of prayer.13 The standard attributes of Faith—a cross and chalice—are absent, however, and it is more likely that this figure is meant to symbolize Hope, who is usually shown with her hands joined in prayer, as in Antonio del Pollaiuolo’s figure from the Mercanzia Virtues or in representations of the Seven Virtues by Pesellino (and Lo Scheggia).14 The crown depicted against the sky background in the Yale panel is not a standard emblem of any of the cardinal or theological Virtues, although it does appear in Giotto’s grisaille allegory of Hope in the Arena Chapel.15 It is possible that the crown is included here as an allusion to the text of Proverbs 12:14, which states that a good wife is a crown to her husband.

Publishing an image of the Yale cassone in 2005, Everett Fahy recorded an attribution for it to Apollonio di Giovanni, although he had earlier proposed that the lid might have been painted by Andrea di Giusto.16 Only in 2008, while the chest was being prepared for loan to an exhibition at Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, Maine, was it recognized that the structure of the cassone was not a pastiche, assembled from unrelated parts of different chests. On that occasion and during subsequent cleaning by Nikolaus (2016–18), it was determined that the front and end panels were painted by a single artist and that the same hand was responsible for a cassone panel representing scenes from the Aeneid in the Seattle Art Museum (fig. 6). The Seattle cassone, which was attributed to Paolo Uccello by Fahy, had, like the Yale cassone, formerly been identified as representing scenes from Boccaccio’s Teseida.17 The present author argued instead that it portrayed the landing of Aeneas’s fleet on the shores of the Tiber and the subsequent battle with King Turnus of Latium and his allies, Messapus and Camilla, at the head of her army of Volscian warriors. A pendant to the Seattle panel in the Musée des Beaux-Arts at Tours, France (fig. 7), representing the preceding episodes in the story of Camilla, was also correctly attributed by Fahy to Paolo Uccello.18 Comparisons with these works and with the recently rediscovered cassone panel of the battle of Metaurus (fig. 8)19—Uccello’s masterpiece in this genre of domestic painting—definitively establishes the attribution of the Yale chest. The reclining nude on the interior of the lid of the Yale chest may instead be compared to two paintings recently given to Uccello but probably to be identified as products of his workshop, possibly painted by his son, Donato di Paolo: a Virgin and Child with Two Angels formerly in the Carl Hamilton collection, New York, and a Virgin and Child in a Landscape (fig. 9) in the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.20

The figural and compositional similarities between these panels and the Yale cassone not only confirm their identity of authorship but also are sufficiently compelling to argue for a general similarity of date. Heraldry within the Seattle and Tours paintings indicate that the chests they once decorated were commissioned to celebrate the wedding of Francesco d’Antonio Antinori and Francesca di Tommaso Soderini in 1470. The other chests are not firmly datable, but comparison to works by Uccello confidently situated in proximity to the Seattle and Tours panels—above all, the predella in the Museo Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino (ca. 1468), the Hunt in the Forest in the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford (ca. 1465–70),21 or the Saint George and the Dragon (1465) in the Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris22—indicates that a date within the decade of the 1460s, probably in the second half of that decade, is highly likely for the Yale cassone as well.23

No overt heraldic references are embedded among the decorative motifs within the battle scene on the front of the Yale cassone, as they are in the Seattle and Tours panels or in another cassone front by Paolo Uccello in the Landesmuseum, Hannover, Germany, representing scenes from the Aeneid (fig. 10).24 It is possible that coats of arms were once attached to the corner pilasters of the chest, which, in their present state, are modern restorations. It is, however, also possible that a disguised heraldic device, similar to the stags’ heads in the Tours cassone symbolizing the arms of the Soderini family, may have been incorporated into the battle scene. If the battle can be identified as that between Achilles and Penthesileia before the walls of Troy, which occurred in the tenth year of the war, there is no reason for the galley at the left to be depicted in full sail while it is empty of crew. A billowing sail was the impresa of the Rucellai family, and it is known from the Zibaldone of Giovanni Rucellai that among the possessions in the family palazzo were paintings by Paolo Uccello.25 It was argued by the present author that these might have been cassone paintings and may possibly have been a pair of panels in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, bearing the devices of the Rucellai and the Medici, probably commissioned as part of the trousseau of Nannina di Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici on the occasion of her marriage to Bernardo Rucellai in 1466.26 These panels were painted in Uccello’s workshop but are not autograph works by the master. It is equally possible that the Yale cassone and its still-missing companion chest may have been the works referenced by Giovanni Rucellai. —LK

Published References

Borenius, Tancred. “Some Italian Cassone Pictures.” In Italienische Studien: Paul Schubring zum 60. Geburtstag gewidmet, 1–9. Leipzig, Germany: Hiersemann, 1929., 6, figs. 3–5, 7; Sizer, Theodore. “An Italian Cassone.” Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 6, no. 2 (June 1934): 24–25., 24–25; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 140–41; Callmann, Ellen. Apollonio di Giovanni. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974., 28n17, fig. 217; Watson, Paul F. “A Preliminary List of Subjects from Boccaccio in Italian Painting, 1400–1550.” Studi sul Boccaccio 15 (1985–86): 149–66., 162; Baskins, Christelle. Cassone Painting, Humanism, and Gender in Early Modern Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988., 35; Branca, Vittore. “Nuove segnalizioni di manoscritti e dipinti.” Studi sul Boccaccio 17 (1988): 99–100., 99; Callmann, Ellen. “Subjects from Boccaccio in Italian Painting, 1375–1525.” Studi sul Boccaccio 23 (1995): 19–78., 37; Fahy, Everett. “Lorenzo Lotto, Venus and Cupid.” In The Wrightsman Picures, ed. Everett Fahy, 6–9. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005., 8; Baskins, Cristelle, ed. The Triumph of Marriage: Painted Cassoni of the Renaissance. Exh. cat. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2009., 100n6; Wegner, Susan E. “Unpacking the Renaissance Marriage Chest: Ideal Images and Actual Lives.” In Beauty and Duty: The Art and Business of Renaissance Marriage, 10–49. Exh. cat. Brunswick, Maine: Bowdoin College Museum of Art, 2008., 21, 22n20, 23–24, 50, 100n6; Franklin, Margaret. “Boccaccio’s Amazons and Their Legacy in Renaissance Art: Confronting the Threat of Powerful Women.” Woman’s Art Journal 31, no. 1 (Spring–Summer 2010): 13–20., 13–20; Kanter, Laurence. “A Cassone Painted in the Workshop of Paulo [sic] Uccello and Possibly Carved in the Workshop of Domenico del Tasso.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin (2010): 114–18., 114–17; Capretti, Elena. “‘Fece in Fiorenza molti quadri a più cittadini, sparsi per le loro case’: Venere, Marte e Cupido e altri dipinti da camera con ‘storie di favole.’” In Piero di Cosimo, 1462–1522: Pittore eccentrico fra Rinascimento e Maniera, ed. Elena Capretti et al., 90–105. Exh. cat. Florence: Galleria degli Uffizi, 2015., 91, 93, fig. 3; Franklin, Margaret. “Imagining and Reimagining Gender: Boccaccio’s Teseida delle nozze d’Emilia and Its Renaissance Visual Legacy.” In “The Short Story and the Italian Pictorial Imagination, from Boccaccio to Bandello and Beyond.” Special issue, Humanities 5, no. 1 (2016), https://doi.org/10.3390/h5010006., n.p.; Compton, Rebekah. Venus and the Arts of Love in Renaissance Florence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021., 63–67, 84n51, 85nn57, 60, 86n61

Notes

-

Sizer, Theodore. “An Italian Cassone.” Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 6, no. 2 (June 1934): 24–25., 24–25. ↩︎

-

Borenius, Tancred. “Some Italian Cassone Pictures.” In Italienische Studien: Paul Schubring zum 60. Geburtstag gewidmet, 1–9. Leipzig, Germany: Hiersemann, 1929., 6. ↩︎

-

Borenius knew the Chalandon cassoni from their reproduction in Schubring, Paul. Cassoni: Truhen und Truhenbilder der italienischen Frührenaissance. Leipzig, Germany: K. W. Hiersemann, 1915., 283, nos. 281–82, pl. 64. In that source, Paul Schubring also catalogued three painted lids showing reclining female nudes: 258, no. 157, pl. 30 (collection of Lord Crawford at Balcarres, Scotland); 264, no. 185, pl. 38 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London, inv. no. 4639-1858, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O132970/cassone-unknown/); and 284, no. 290, pl. 69 (Somerset collection, Eastnor Castle, Herefordshire, England). ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 140–41; and Callmann, Ellen. Apollonio di Giovanni. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974., 28n17. ↩︎

-

Callmann, Ellen. “Subjects from Boccaccio in Italian Painting, 1375–1525.” Studi sul Boccaccio 23 (1995): 19–78., 37. ↩︎

-

Watson, Paul F. “A Preliminary List of Subjects from Boccaccio in Italian Painting, 1400–1550.” Studi sul Boccaccio 15 (1985–86): 149–66., 162; Branca, Vittore. “Nuove segnalizioni di manoscritti e dipinti.” Studi sul Boccaccio 17 (1988): 99–100., 99; Baskins, Christelle. Cassone Painting, Humanism, and Gender in Early Modern Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988., 100n6; and Wegner, Susan E. “Unpacking the Renaissance Marriage Chest: Ideal Images and Actual Lives.” In Beauty and Duty: The Art and Business of Renaissance Marriage, 10–49. Exh. cat. Brunswick, Maine: Bowdoin College Museum of Art, 2008., 23, 50. ↩︎

-

Callmann, Ellen. “Subjects from Boccaccio in Italian Painting, 1375–1525.” Studi sul Boccaccio 23 (1995): 19–78., 37. ↩︎

-

Freuler, Gaudenz. “Manifestatori delle cose miracolose”: Arte italiana del ’300 e ’400 da collezioni in Svizzera e nel Liechtenstein. Exh. cat. Lugano-Castagnola, Switzerland: Fondazione Thyssen-Bornemisza, 1991., 244–47. ↩︎

-

Franklin, Margaret. “Boccaccio’s Amazons and Their Legacy in Renaissance Art: Confronting the Threat of Powerful Women.” Woman’s Art Journal 31, no. 1 (Spring–Summer 2010): 13–20., 14, 19n8. ↩︎

-

Kanter, Laurence. “A Cassone Painted in the Workshop of Paulo [sic] Uccello and Possibly Carved in the Workshop of Domenico del Tasso.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin (2010): 114–18.; and Compton, Rebekah. Venus and the Arts of Love in Renaissance Florence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.. ↩︎

-

Franklin, Margaret. “Boccaccio’s Amazons and Their Legacy in Renaissance Art: Confronting the Threat of Powerful Women.” Woman’s Art Journal 31, no. 1 (Spring–Summer 2010): 13–20., 19n8. ↩︎

-

Courtauld Institute of Art, London, inv. no. F.1947.LF.4; and Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, inv. no. 46.13.1. See Baskins, Cristelle, ed. The Triumph of Marriage: Painted Cassoni of the Renaissance. Exh. cat. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2009., 100n6. ↩︎

-

Borenius, Tancred. “Some Italian Cassone Pictures.” In Italienische Studien: Paul Schubring zum 60. Geburtstag gewidmet, 1–9. Leipzig, Germany: Hiersemann, 1929., 6; and Sizer, Theodore. “An Italian Cassone.” Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 6, no. 2 (June 1934): 24–25., 24–25. ↩︎

-

Birmingham Museum of Art, Ala., inv. no. 1961.102, https://www.artsbma.org/collection/seven-virtues/; and Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, inv. no. 64967, https://www.museunacional.cat/en/colleccio/seven-virtues/anton-francesco-dello-scheggia/064967-000, respectively. See Baskins, Cristelle, ed. The Triumph of Marriage: Painted Cassoni of the Renaissance. Exh. cat. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2009., 96–103; and Freyhan, R. “The Evolution of the Caritas Figure in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 11, no. 1 (1948): 68–86., 68–86. ↩︎

-

See Lange, Henrike Christiane. “Relief Effects: Giotto’s Triumph.” Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 2015., esp. 81–92. See also Lange, Henrike Christiane. Giotto’s Arena Chapel and the Triumph of Humility. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022., esp. figs. 1.15–.16, 1.19–.20, 2.9, 4.29, and 5.3–.4; and Lange, Henrike Christiane. “Giotto’s Triumph: The Arena Chapel and the Metaphysics of Ancient Roman Triumphal Arches.” I Tatti Studies 25, no. 1 (Spring 2022): 5–38.. ↩︎

-

Fahy, Everett. “Lorenzo Lotto, Venus and Cupid.” In The Wrightsman Picures, ed. Everett Fahy, 6–9. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005., 8; and Fahy, opinion, reported by Carl Strehlke, 2002, curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

Fahy’s opinion is recorded in Ishikawa, Chiyo. The Samuel H. Kress Collection at the Seattle Art Museum. Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 1997., 53–54. ↩︎

-

For a discussion of the subject of the Seattle cassone front and its pendant in Tours, the identification of their patron and date, and a defense of their attribution to Paolo Uccello, see Kanter, Laurence. “The ‘cose piccole’ di Paolo Uccello.” Apollo Magazine 152, no. 462 (August 2000): 11–20., 11–20. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. “Quadri senza casa: Il quattrocento fiorentino, I.” Dedalo 12, no. 7 (1932): 512–41., 524–28, 530–31; and Kanter, Laurence. “The ‘cose piccole’ di Paolo Uccello.” Apollo Magazine 152, no. 462 (August 2000): 11–20., 15. The painting reappeared at auction at Sotheby’s, London, July 28, 2020, lot 23, and is now in a private English collection. ↩︎

-

Minardi, Mauro. Paolo Uccello. Milan: Prima, 2017., 318–20. Minardi rejected the attribution to Uccello of any cassone panel, but his estimation of the quality of these two Virgin and Child compositions relative to that of the cassoni discussed here should be reversed. Equally, his rejection of the profile portrait at the Isabella Stuart Gardner Museum (inv. no. P27W58, http://gardnermuseum.org/experience/collection/12396/) as a work by Uccello is unsustainable. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. WA1850.31, https://collections.ashmolean.org/object/373613. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. MJAP-P 2248, https://www.musee-jacquemart-andre.com/en/works/saint-george-and-dragon. ↩︎

-

Dating of the Jacquemart-André Saint George follows the discovery by James Beck of a document likely to relate to it. His argument that the Saint George and the Dragon in the National Gallery, London (inv. no. NG6294, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/paolo-uccello-saint-george-and-the-dragon) must postdate the Paris painting is fallacious, based on a presumptive development in Uccello’s mastery of three-dimensional illusion rather than a demonstrable preference in his late career for more mannered compositions. See Beck, James. “Paolo Uccello and the Paris Saint George, 1465: Unpublished Documents, 1452, 1465, 1474.” Gazette des beaux-arts 93 (1979): 1–5., 1–5. ↩︎

-

Decorative elements in this painting may refer to the Nasi and Pollini families of Florence, but this cannot be confirmed, and a union between these families has not yet been discovered. ↩︎

-

Perosa, A., ed. Giovanni Rucellai ed il suo Zibaldone. Vol. 1. London: Warburg Institute, 1960., 24. ↩︎

-

Inv. nos. PE 87, http://collections.lesartsdecoratifs.fr/scene-de-bataille-0; and PE 88, http://collections.lesartsdecoratifs.fr/scene-de-triomphe. See Kanter, Laurence. “The ‘cose piccole’ di Paolo Uccello.” Apollo Magazine 152, no. 462 (August 2000): 11–20., 20n6. ↩︎