Dan Fellows Platt (1873–1937), Englewood, N.J., by 1923; Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, by 1926

The panel support, of a vertical wood grain, is 1.6 centimeters thick and has not been thinned nor cut on any side. It preserves its original engaged frame moldings, 8 millimeters thick, and remnants of painted porphyry decoration along its outer top and left edges; the outer right edge preserves an original gesso coating but no evidence of painted decoration. There are two holes for a rope hanging strap pierced at the top center of the back of the panel, and candle burns at the top of the left outer edge and just left of center on the bottom outer edge. The gilding and paint surfaces are heavily abraded. Bolus is visible throughout the gold ground, and all flesh tones are worn to reveal the green preparatory layers underneath. The Christ Child’s robe has lost all its painted and glazed decoration, except for a thin strip along the profile of the garment where it overlaps the hands and robe of Saint Jerome. The Virgin’s blue robe and green lining have been all but destroyed by solvent damage. By contrast, the Virgin’s white veil and the robes of Saints Jerome and Bernardino are well preserved. The painting was cleaned by Andrew Petryn in 1954.

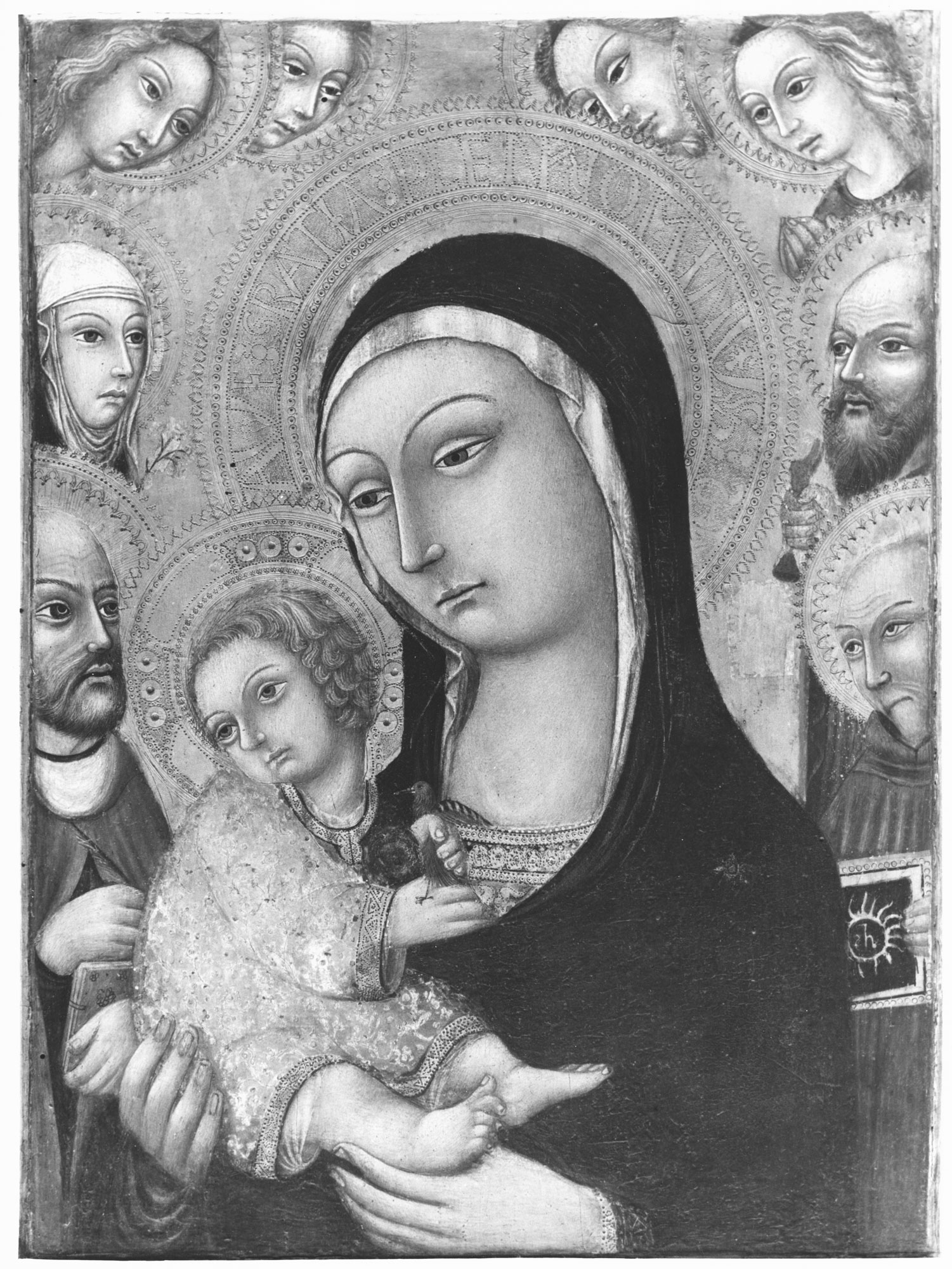

The painting shows the Virgin, bust length and turned three-quarters to the viewer’s left, holding the Christ Child seated in the palm of her right hand, her left hand supporting His right foot and ankle. The Child wears a gilded robe probably once painted white with a decoration of sgraffito flowers, of which little more than the bolus preparatory layer remains. He holds a goldfinch before Him with both hands and turns back to look out of the composition over His right shoulder. Behind Him at the lower left is Saint Jerome, dressed in cardinal’s red and holding a book and quill. Opposite Jerome at the lower right is Saint Bernardino, in a brown Franciscan habit, holding before him a tablet emblazoned with the monogram of Christ, IHS, in a sunburst. Above and behind Saint Jerome at the left is Saint Catherine of Siena, wearing a Dominican habit and holding a spray of flowers. The identity of the saint opposite her on the right is not completely clear, as the attribute he holds is only indistinctly legible. If it is the hilt of a sword, the blade extending down past Saint Bernardino’s shoulder, he could be understood to represent Saint Paul. In other paintings by Sano di Pietro, however, Paul regularly holds his sword turned upward. Precleaning photographs of the Yale panel (fig. 1) show this figure holding a rustic wooden staff with a bell tied to its handle, indicating a probable identity as Saint Anthony Abbot. The heads of four angels, all wearing red diadems, close off the picture field at the top.

The composition is typical of an exceptionally large class of devotional objects in which Sano di Pietro specialized, producing innumerable close variants but never exact replicas over the last thirty years of his career. These always feature a large, bust-length image of the Virgin holding her Child before her, sometimes filling the entire picture field, sometimes with two or more saints and pairs of angels—always on a smaller scale than the principal figures—crowded around the margins. Compositions in which, as here, the Child is turned to look back out of the painting over His right shoulder are especially numerous, with high-quality examples in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.;1 the Robert Lehman Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (fig. 2); the Berenson Collection at Villa I Tatti, Settignano;2 the Lindenau-Museum Altenburg, Germany;3 the Art Institute of Chicago;4 the Christ Church Gallery, Oxford;5 the Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest;6 and elsewhere. All of these are based on a single cartoon or patrono, with minor adjustments to the placement of the Virgin’s hands and the Child’s feet or hands. In the Altenburg version, the composition is reversed. In some, the Child is occupied with the hem of His mother’s cloak; in some, He holds a pomegranate, a symbol of the Passion; and in some, He plays with a goldfinch, symbol of the human soul but also an allusion to the Resurrection.7 Nearly all are characterized by a high level of craftsmanship and elaborate ornamentation of the gold ground. If the Virgin’s halo is lettered rather than simply filled with combinations of punch tools, the inscription is always AVE GRATIA PLENA DOMINUS TECUM (Hail [Mary] full of grace, the Lord is with you).

Regardless of the compositional formula adopted for the Virgin and Child, a singular feature of this class of paintings by Sano, of which the Yale panel is again a typical example, is the exceptional number of them that include Saints Jerome and Bernardino in the places of honor to the left and right of the principal figures. Over forty examples are known, only a few of which include other saints in addition to these two. This group is roughly evenly divided between those portraying Saint Jerome as a cardinal, as seen here, and those that instead show him dressed as a penitential hermit with a string of beads or a rock in his hand. The latter have been explained as a reference to the cult of Saint Jerome espoused by the Order of the Gesuati in Siena.8 Sano di Pietro was regularly patronized by the Gesuati, painting three altarpieces for them, but it is difficult to imagine one relatively small monastic order monopolizing his production of private devotional panels for its members, and suggesting so fails to explain why Jerome is inevitably paired with Saint Bernardino. A more likely source for these commissions, though perhaps not an exclusive one, would seem to be the Confraternity of Saint Jerome, established in 1428 by members of the wealthier classes in Siena. In 1443, with an expanded dedication to Saints Jerome and Francis, the society was conceded an oratory chapel beneath the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala opposite the cathedral. Upon the death of Saint Bernardino in 1444, the confraternity aggregated his name to their title,9 and their religious duties were officiated by friars from Bernardino’s community at the Osservanza. A later member of this confraternity, Pietro di Francesco degli Orioli, also produced an unusual number of paintings for private devotion featuring the titular saints of the brotherhood.10

The few authors to have mentioned the Yale panel all refer to it as a product of Sano di Pietro’s workshop, an evaluation that is no doubt correct but requires some qualification. The facial features of all ten figures in the composition are simplified, almost caricatural reprises of Sano’s standard types, but they do not correspond exactly in style to those in any other painting by the artist known to this writer. They are instead directly inspired by the heads painted by Sassetta in his fresco of the Assumption of the Virgin on the Porta Romana in Siena (fig. 3), a work left incomplete by the artist at his death in 1450 and subsequently finished by Sano di Pietro. The punch tools used to decorate the gold ground in the Yale panel were all property of Sano’s workshop but are not deployed strictly in his manner: in no other painting by that punctilious artist does the lettering in the Virgin’s halo diverge from an orientation following the radius of the nimbus and slip toward a vertical orientation—as do the first five letters of DOMINVS here—and in no other halo by Sano is the final A in PLENA omitted. Wolfgang Loseries has suggested that Sano’s habit of forming the G in GRATIA with two confronted half-circles, as here, disappears from securely dated works after 1456, to be replaced by a more conventional capital letter.11 The precision of this change as a factor in determining the chronology of Sano’s work cannot be taken too seriously, but it is doubtless a reliable general indicator of an earlier or later date for any given painting. The Yale panel cannot predate 1461, when Catherine of Siena, portrayed here above Saint Jerome, was canonized, but neither is it likely to have been painted many years after that. All these factors considered together imply that this is not a “standard” example of the output of Sano’s workshop but is instead an unusual work by an artist employed perhaps only temporarily with Sano. If this were so, a prime candidate for such an artist would be the so-called Master 185 (see Master 185, Virgin and Child Enthroned), who is otherwise not known to have painted any figures on this scale but whose indices of style all tend in this direction. —LK

Published References

Gaillard, Émile. Un peintre siennois au XV siècle: Sano di Pietro, 1406–1481. Chambéry, France: M. Dardel, 1923., 203; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 9. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1927., 532, 527n2; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 205, 320, no. 155; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 182, 600; Charles Seymour, Jr., in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 8

Notes

-

Inv. no. 1939.1.274, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.417.html. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. P 101. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 72 (38). ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1933.1027, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/16212/virgin-and-child-with-saints-jerome-bernardino-of-siena-and-angels. ↩︎

-

See Shaw, James Byam. Paintings by Old Masters at Christ Church, Oxford. London: Phaidon, 1967., 47, no. 32. ↩︎

-

See Boskovits, Miklós. “Un nome per il Maestro del Trittico Horne.” Saggi e memorie di storia dell’arte 27 (2003): 57–70., 620n8. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1210, http://mfab.hu/artworks/9972/. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. “Un nome per il Maestro del Trittico Horne.” Saggi e memorie di storia dell’arte 27 (2003): 57–70., 617, 620nn10–11. Boskovits’s claim that all the versions in which the Christ Child is painted next to Saint Jerome show the latter in hermit’s robes is mistaken. See also Wolfgang Loseries, in Boskovits, Miklós, and Johannes Tripps, eds. Maestri senesi e toscani nel Lindenau-Museum di Altenburg. Exh. cat. Siena: Protagon, 2008., 135, 136nn7–8. ↩︎

-

Alessi, Cecilia. La confraternita ritrovata: Benvenuto di Giovanni e Girolamo di Benvenuto nello Spedale Vecchio di Siena. Siena: Ali, 2003., 29–32. Daniela Gallavotti Cavallero (in Gallavotti Cavallero, Daniela. Lo spedale di Santa Maria della Scala in Siena: Vicenda di una committenza artistica. Pisa: Pacini, 1985., 405) reported, perhaps with greater credibility, that the confraternity adopted Saint Bernardino in their title only in 1450, upon his canonization. ↩︎

-

Laurence Kanter, in Christiansen, Keith, Laurence Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke. Painting in Renaissance Siena, 1420–1500. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988., 335–37. ↩︎

-

Loseries, in Boskovits, Miklós, and Johannes Tripps, eds. Maestri senesi e toscani nel Lindenau-Museum di Altenburg. Exh. cat. Siena: Protagon, 2008., 134. ↩︎