James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

The panel support, of a vertical wood grain, comprises three planks: two boards, each approximately 11 centimeters wide, flanking a central board approximately 38 centimeters wide. It has been thinned to a depth of 1 centimeter and was waxed and cradled by Hammond Smith in 1915, but it appears not to have been trimmed along its outer edges, except possibly along the top, where the profile of the panel is slightly irregular. The original engaged frame is missing, but remnants of a barb of gesso along all four sides of the picture field indicate that this has not been altered in size or shape. The seams between the planks are well adhered and have not resulted in any paint loss. Six vertical splits descend a short distance from the top edge, but only the split furthest right—which passes through the wings of the pair of angels in the upper-right corner of the composition and descends as far as the waist of Saint Francis at the bottom right—has provoked any appreciable paint loss. The gilding throughout is beautifully preserved. The paint surface has been abraded from aggressive cleaning, most recently by Andrew Petryn during a treatment of 1958–60, but it is generally in good condition. Terra verde underpainting is strongly visible through some of the flesh tones. Scattered minor losses, principally in the heads of the angels at the top, were discretely inpainted by Anne O’Connor in 2003. The Dove of the Holy Spirit is not painted in a conventional tempera technique and may be a later addition or an early repair: incomplete mordant gilt rays are still partially visible radiating downward from the spot it occupies.

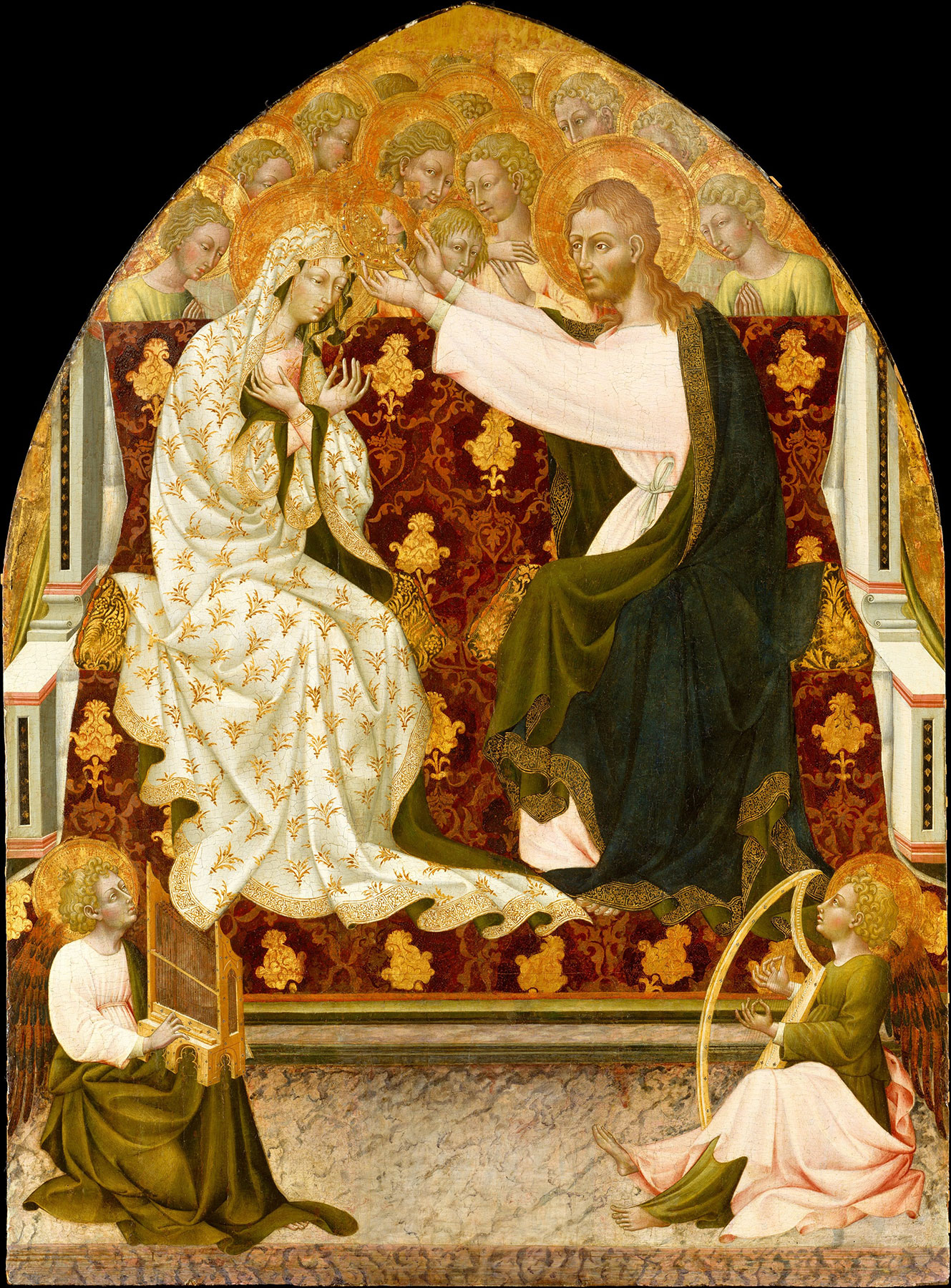

The number and frequency of references to the Yale Coronation of the Virgin between 1860 and 1932 reflect the popularity of Sienese fifteenth-century paintings with collectors and amateurs before the Second World War, as well as the elevated profile of this painting within that category. The paucity of references to it in the following forty years does not indicate a scholarly change of its status so much as a decline of general interest in the field, further underscored by the complete absence of citations over the past fifty years. In every instance—with the conspicuous and inexplicable exception of Charles Seymour, Jr., who considered it a product of the artist’s workshop1—the painting is referred to as an autograph work by Sano di Pietro of distinguished quality. Particular note has been made of its brilliant palette, reminiscent of manuscript illumination, and its animated composition, enlivened by the beautifully executed textile patterns behind and beneath the central figures, Christ and the Virgin, seated side by side on a high-backed throne. Christ places a crown on His mother’s head as she joins her hands reverently before her. Below the throne in the foreground are two angels kneeling on an Anatolian carpet, playing a portative organ (left) and a viol (right); a vase of white and red roses stands on the carpet between them. Two pairs of angels peer over the back of the throne, each pair with a music-making angel in red flying above it: that on the left plays a harp, that on the right a lute. The Dove of the Holy Spirit hovers against a blue sky directly in the center of the composition at the top, while six more angels, three on either side, fill out the upper corners of the painted surface.

Sixteen saints stand alongside the throne, four ranks of two on either side. All are painted on a slightly larger scale than the angels but considerably smaller than Christ or the Virgin. Before and below them, in the lower corners of the composition, kneel Saints Bernardino (left) and Francis (right). The first row of saints is all female, two holding martyr’s palms and two (on the right) wearing crowns. Above and behind these are the four Fathers of the Church: Saints Jerome and Augustine on the left, Ambrose and Gregory on the right.2 A fragmentary halo is visible behind and between the latter pair, suggesting that the four figures are meant to be emblematic representatives of the larger order of Confessors, one of the choirs of saints invoked in the hymn “Te Deum Laudamus” recited on the Feast of All Saints. The third row of saints includes Saints John the Evangelist and Peter on the left. The pair opposite them is probably also meant to portray apostles. Although neither bears a distinguishing attribute, the figure furthest right resembles the type usually employed by Sano di Pietro to represent Saint Bartholomew, and the figure alongside him could be Saint Paul. A fragmentary halo appears between both pairs of figures in this row, once again implying that they are meant to be emblematic of the full chorus of apostles and Evangelists. The top row of saints may be prophets and patriarchs; all are elderly and bearded, but none bears an identifying attribute. Partially visible arcs of six more haloes on the right and two on the left suggest a crowd of holy figures completing the court of Heaven in attendance at the scene of the Coronation. Of the conventional orders of saints, only the martyrs are missing. Two of the virgins in the front row carry martyr’s palms, but others were probably intended to be suggested by the crowd of partial and overlapping haloes at the back. Conspicuous in their absence are any monastic saints other than the two Franciscans in the foreground and any figure who could plausibly be identified as Saint John the Baptist.

The subject of the Coronation of the Virgin enjoyed “a remarkable increase in popularity” in Siena around the middle of the fifteenth century, “symbolized by the total renewal by Domenico di Bartolo and Sano di Pietro in 1445 of a huge fresco with the Coronation painted by Lippo Vanni in 1352 on the left wall of the Sala del Biccherna of the Palazzo Pubblico” (fig. 1).3 An altarpiece by Giovanni di Paolo in Sant’Andrea, Siena, is dated 1445, and another in the Robert Lehman Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (fig. 2), must date shortly afterward. Sano di Pietro painted two monumental versions of the theme. One, an altarpiece now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena (fig. 3), has tentatively been identified with a commission of 1451 for a chapel in the Palazzo Pubblico.4 It follows closely the composition of Giovanni di Paolo’s altarpiece in the Lehman Collection, reproducing even the textile pattern on the cloth of honor lining the Virgin’s throne. The other, in Gualdo Tadino, includes smaller kneeling figures of Saint Jerome and the Blessed Giovanni Colombini in the foreground and is dated to 1473.5 One further example of a Coronation of the Virgin by Sano di Pietro, again in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena, was probably designed as the pinnacle to an altarpiece.6 Painted with a gold ground and a slightly arched top, it includes no ancillary figures, yet the punched margin of the gilding implies that it has not been reduced in size.7

The Yale Coronation follows most closely the general composition of the Gualdo Tadino panel of 1473, simplifying its ornament and adding a carpeted platform beneath the feet of Christ and the Virgin nearly identical to that introduced in the 1445 fresco in the Palazzo Pubblico (see fig. 1). The rectangular format of the Yale panel, however, is a novelty, conforming to none of the arched picture fields of its models and recalling instead one of the types of devotional panels showing the Virgin and Child with saints and angels that the artist produced in great numbers. The latter, as a rule, are highly static images, crowding a variable number of half-length or bust-length figures into a limited pictorial space, and they are generally not as large as the Yale panel. Only in unusual cases, such as that of a Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine from the Kress Collection in the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College, Massachusetts,8 are they animated by a narrative content or conceived on the imposing scale of the Yale panel. In this regard, the Yale Coronation bears a casual resemblance to another innovative type of panel produced by Sano di Pietro, a small anconetta that combines the content of an altarpiece polyptych with the scale of a private devotional tabernacle. Two particularly fine examples in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena, show a Virgin and Child Enthroned surrounded by numerous standing saints in their main rectangular picture fields and, in a mixtilinear gable above, the Crucifixion with, in the one case, the Annunciation (fig. 4) and, in the other, scenes of the Agony in the Garden and the Noli me Tangere.9 It cannot be ascertained whether the Yale panel might have been completed by a narrative gable. The presence of a barb along its top edge indicates that an engaged molding was applied there, unlike the two anconette in Siena. The oddly painted Dove of the Holy Spirit hovering above the scene, however, seems to have been added later, possibly to justify the appearance of golden rays in this area emanating downward from what might, hypothetically, have been a figure of God the Father in an attached pinnacle. —LK

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 47, no. 44; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 54, no. 50; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 19, no. 50; Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 143, pl. 7; Berenson, Bernard. The Central Italian Painters of the Renaissance. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1897., 175; Crowe, Joseph Archer, and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle. A History of Painting in Italy, Umbria, Florence, and Siena from the Second to the Sixteenth Century. Vols. 1–4, ed. Robert Langton Douglas. Vols. 5–6, ed. Tancred Borenius. London: J. Murray, 1903–14., 5:174; Perkins, F. Mason. “Pitture senesi negli Stati Uniti.” Rassegna d’arte senese 1, no. 2 (1905): 74–78., 76; Rankin, William. Notes on the Collections of Old Masters at Yale University, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Fogg Museum of Harvard University. Wellesley, Mass.: Department of Art, Wellesley College, 1905., 10; Berenson, Bernard. The Central Italian Painters of the Renaissance. 2nd rev. ed. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1909., 239; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 157–58, no. 60; Gaillard, Émile. Un peintre siennois au XV siècle: Sano di Pietro, 1406–1481. Chambéry, France: M. Dardel, 1923., 174n1, 204; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 9. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1927., 521, fig. 332; Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 7; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 500; Edgell, George Harold. A History of Sienese Painting. New York: Dial, 1932., 212; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:376; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 202–4, no. 153; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 181, 599; Vertova, Luisa. “The New Yale Catalogue.” Burlington Magazine 115 (March 1973): 159–61, 163., 160

Notes

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 202–4, no. 153. ↩︎

-

Seymour incorrectly identified these as “the four patron bishop-saints of Siena” (Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 204). Luisa Vertova pointed out that the patron saints of Siena—Ansanus, Crescentius, Victor, and Sabinus—are three young martyrs and one elderly bishop, whereas these are a cardinal, two bishops, and a pope (Vertova, Luisa. “The New Yale Catalogue.” Burlington Magazine 115 (March 1973): 159–61, 163., 160). She, unfortunately, identified the papal figure as Saint Clement rather than Saint Gregory. ↩︎

-

van Os, Henk. Sienese Altarpieces, 1215–1460: Form, Content, Function. Vol. 2, 1344–1460. Groningen, Netherlands: Egbert Forsten, 1990., 158. Henk van Os mistakenly reports the date of Domenico di Bartolo’s and Sano di Pietro’s work on this fresco as 1455. ↩︎

-

Cairola, Aldo, and Enzo Carli. Il Palazzo Pubblico di Siena. Rome: Editalia, 1963., 204. ↩︎

-

Museo Civico Rocco Flea, Gualdo Tadino; see Fototeca Zeri, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna, inv. no. 16420. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 223. ↩︎

-

Piero Torriti incorrectly dates this fragment after 1470 and adduces it as an example of the artist’s decadence (Torriti, Piero. La Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena. Vol. 1, I dipinti dal XII al XV secolo. Genoa: Sagep, 1977., 295). Unusually, the stenciled pattern employed to decorate the cloth of honor on the back and seat of the throne continues without interruption onto the Virgin’s draperies. The style of the painting is much closer to that of works from around 1460, and its quality is relatively high. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. AC 1961.83. ↩︎

-

For the second example, see inv. no. 273. ↩︎