Stefano Bardini (1836–1922), Florence; sale, American Art Association, New York, April 23–27, 1918, lot 447; Richard Ederheimer (1878–1959), New York; Elia Volpi (1858–1938), Florence; Robert Lehman (1891–1969), New York

The panel support is composed of three vertical boards, approximately 6, 16, and 8 centimeters wide, left to right (viewed from the front), and a horizontal board, 2 centimeters wide, laid across the top of these. The boards have been thinned to a depth of 5 millimeters and cradled. Two baluster-shaped total losses revealing exposed wood extend the full height of the panel, one bisected by the right edge, the other 4 centimeters on center from the left edge. The paint surface has suffered extensive losses along splits in the panel and from scratching, but it is surprisingly little abraded, retaining numerous passages of original impasto. Losses were reconstructed in tratteggio by Irma Passeri in a treatment of 2012–14; large areas of exposed gesso at the bottom and smaller areas along the immediate profile of the balusters were merely toned back. The head of Antaeus is mostly lost, and the coat of arms is interrupted by a split through the upper field and total loss of the bottom field.

According to Apollodorus (Bibliotheca 2.5:11) and Diodorus Siculus (Bibliotheca historica 4), Hercules encountered the giant Antaeus on his return from securing the apples of immortality in the Garden of the Hesperides, the eleventh of his twelve labors for King Eurystheus. Antaeus, tyrant of Libya and a son of Gaea and Neptune, was invincible while any part of him remained in contact with the earth, his mother. To defeat him, Hercules held him aloft in a strangling grip until he weakened and died. In the Yale panel, Hercules is seen in three-quarter profile from behind, standing in a landscape with his legs braced apart. He crushes Antaeus to his chest while the giant struggles to break his grip. Both figures are portrayed nude. A shield with a coat of arms hangs from a tree in the right middle ground. The composition is closed off at either side by baluster-shaped lacunae, where half-round carved ornament was undoubtedly originally attached directly to the panel support. The right edge of the panel cuts the right baluster almost exactly in half, whereas the outline of the left baluster is preserved nearly whole, the blue sky of the landscape continuing at the upper left, beyond the top half of the baluster. An indistinct dark line at the farthest edge of this extension of the sky suggests that another tree and hanging shield of arms were cropped there.

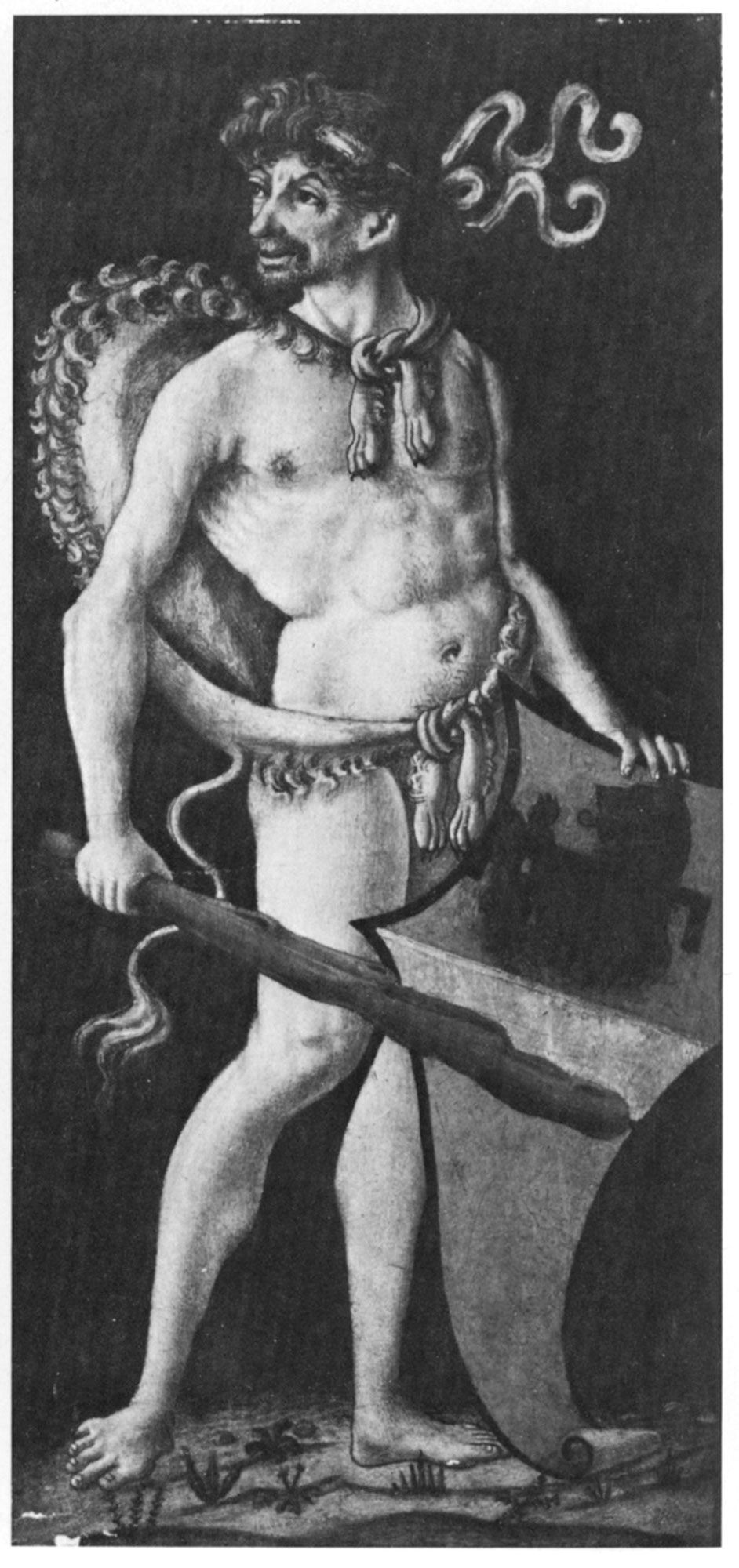

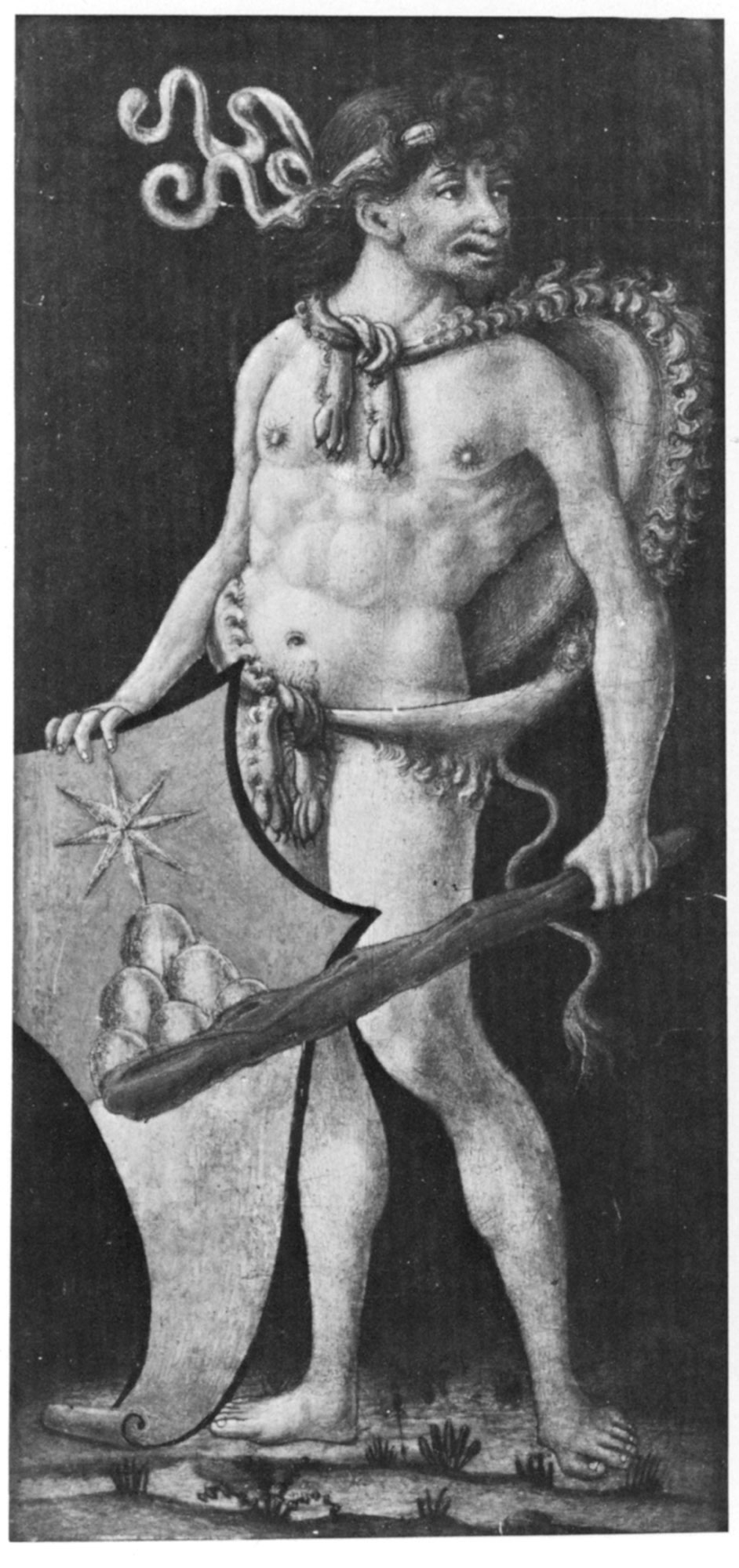

The size, shape, subject, and heraldic content of this panel suggest that it functioned originally as the end panel of a painted cassone. The coat of arms, previously unidentified but certainly those of the Bellanti of Siena, would thus refer either to the family of the bride or groom in an important marriage alliance and would have been paired with the arms of the other family, either in a scene alongside this one or occupying the opposite end panel of the chest, or both. Following the conventional premise that cassoni were always or nearly always commissioned in pairs, there is a strong presumption that two panels on loan to the Institute for Art History, University of Groningen, the Netherlands, from the Dienst voor’s Rijks Verspreide Kunstvoorwerpen (figs. 1–2), may have formed part of the same pair of chests. The Groningen panels, which measure 35 by 17 centimeters each, represent two standing figures of Hercules, in mirror image to each other, holding an armorial shield, one with the arms of the Bellanti—corresponding to those on the Yale panel—and the other with the arms of the Chigi.1 Allowing for their closer cropping along all four sides, these dimensions reasonably approximate those of the Yale panel, and all three works relate closely in style. The original wood supports of the Groningen panels were lost when they were transferred to new supports, but horizontal splits through both figures imply that the grain direction ran horizontally and therefore that these panels closed off the front face of the chest in their original configuration. The wood support of the Yale panel is of a vertical grain, more likely to have been encountered on the side rather than on the front of the intact chest.

The Yale and Groningen panels have been persistently attributed to Antonio or Piero del Pollaiuolo or to an assistant in their joint workshop, a reflexive acknowledgment of the association of that studio with painted episodes from the Hercules legend and with images of heroic male nudes. The Yale panel, furthermore, corresponds closely, in reverse, to the design of the small Hercules and Antaeus by Antonio del Pollaiuolo in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence (fig. 3). The correspondence is so close as to imply firsthand familiarity with the Uffizi panel, with its supposed model—a large canvas painted around 1460 for the Palazzo Medici in Florence—or, given the correction of the silhouette to suggest a slight rotation along the group’s vertical axis, a clay or wax maquette of a type represented by the small bronze now in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence (fig. 4).

The first scholar to reject an attribution for any of these paintings to the Pollaiuolo studio was Bernard Degenhart, who suggested that the Groningen panels might instead be the work of an anonymous Sienese master, given that both coats of arms portrayed in them are Sienese.2 An attribution to Matteo di Giovanni was advanced for them in 1988 by the present author, and Andrea De Marchi extended the same attribution to the Yale panel in 1993.3 In attributing the Groningen panels to Matteo di Giovanni, the present author observed that they were probably to be associated with the only known pair of painted cassone fronts by the artist, two episodes from the legend of Camilla: one in the Philadelphia Museum of Art (fig. 5) and the other formerly in the W. H. Woodward collection, last recorded for sale in 1945.4 This association should now be extended to the Yale panel as well, which is particularly close in style to the Philadelphia scene of Camilla leading her Volscian army to the aid of the Latins in battle against Aeneas and his Trojan followers. The Philadelphia panel measures 39.7 by 105.7 centimeters, commensurate in height with both the Groningen and Yale panels.

Robert Langton Douglas, who briefly owned the Groningen panels following the dispersal of the Woodward collection and prior to their sale to Otto Lanz in Amsterdam, proposed an identification of the marriage celebrated by the pairing of their coats of arms as that between Eufrasia di Mariano Chigi and Andrea di Bartolo Meo Bellanti sometime before 1488, the year in which Eufrasia Chigi’s dowry was reported to the Sienese tax authorities. While the exact date of this marriage, and presumably of the commission for Matteo di Giovanni’s cassoni, has not been discovered, it is unlikely to have occurred earlier than ca. 1480, as the bride’s father, Mariano Chigi (1439–1504), founder of the celebrated banking dynasty, was only forty-one in that year, and his oldest son, Agostino, was merely fourteen. The style of the Yale, Groningen (see figs. 1–2), Philadelphia (see fig. 5), and ex-Woodward panels, on the other hand, is consistent with Matteo di Giovanni’s work of the late 1470s and early 1480s, a period bracketed by the Saint Barbara altarpiece of 1479 in the church of San Domenico in Siena and the Massacre of the Innocents of 1482, formerly in the church of Sant’Agostino in Siena and now in the Complesso Museale di Santa Maria della Scala (fig. 6). Retouching of damages in the Groningen panels, however, urges caution in relying on them for a precise dating of the suite of paintings. The coats of arms have been repaired, adding, for example, shading and highlights to the monti and star of the Chigi arms not typically encountered in fifteenth-century heraldry. It is at least hypothetically possible that an intrusive intervention converted the three monti and star of the Savini family to the later, much better-known six monti of the Chigi family. No alliance between the Savini and Bellanti has yet been uncovered. —LK

Published References

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 173, 317, no. 124; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 601; Timothy Verdon, in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 47, no. 40; Scalia, Fiorenza, and Cristina De Benedictis. Il Museo Bardini a Firenze. Milan: Electa, 1984., 124; Alessandro Angelini, in Bellosi, Luciano, ed. Francesco di Giorgio e il Rinascimento a Siena, 1450–1500. Exh. cat. Milan: Electa, 1993. , 144; Fahy, Everett. L’archivio storico fotografico di Stefano Bardini, dipinti-disegni-miniature-stampe. Florence: Bruschi, 2000., 47, 238, no. 397; Wright, Alison. The Pollaiuolo Brothers: The Arts of Florence and Rome. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005. , 535.

Notes

-

Bert Treffers, in van Os, Henk, and Marian Prakken, eds. The Florentine Paintings in Holland, 1300–1500. Exh. cat. Maarssen, Netherlands: Gary Schwartz, 1974. , 100–101. ↩︎

-

Degenhart, Bernard. “Zur Ausstellung der Sammlung Otto Lanz im Rijksmuseum von Amsterdam.” Pantheon 27, no. 1 (1941): 34–40., 36. ↩︎

-

Laurence Kanter, in Christiansen, Keith, Laurence Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke. Painting in Renaissance Siena, 1420–1500. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988., 283; and Andrea De Marchi, in Alessandro Angelini, in Bellosi, Luciano, ed. Francesco di Giorgio e il Rinascimento a Siena, 1450–1500. Exh. cat. Milan: Electa, 1993. , 144. ↩︎

-

Sale, Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York, November 15, 1945, lot 25; Fototeca Zeri, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna, inv. no. 17293. See Laurence Kanter, in Christiansen, Keith, Laurence Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke. Painting in Renaissance Siena, 1420–1500. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988., 283. ↩︎