James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

The panel support, of a vertical wood grain, retains its original thickness, varying from 2.8 to 3.5 centimeters. It is composed of five boards: a wide center plank that tapers from a maximum width of 45.5 centimeters at the top to 44 centimeters at the bottom flanked by two boards at the left, 6.5 and 4 centimeters wide, respectively, from left to right, and two boards at the right, 5.5 and 4 centimeters wide, respectively, from left to right. Two iron hanging rings attached by wire loops driven into the top edge of the center plank are original. The paint surface has been evenly abraded from a harsh cleaning of 1960, above all in the flesh tones—where whites and pinks are preserved, but all the glazed shadows are missing—and in the Virgin’s blue draperies. Gilding in the angels’ haloes is abraded to bolus but elsewhere is well preserved. Red glazes defining the petals of the roses are missing, as are mordant gilt rays around the head of the Virgin. The darker gray pigments in the Dove of the Holy Spirit are pitted with small flaking losses.

The most distinguished of the four works by Benvenuto di Giovanni in Yale’s collection, this notable painting was assigned to Matteo di Giovanni when it was owned by James Jackson Jarves, but its correct attribution to Benvenuto has not been doubted since it was first proposed by William Rankin in 1895.1 Writers have been divided between those who believe it to have been painted in the later 1470s,2 in relation to the altarpieces of 1475 at Montepertuso3 and 1479 in London (see Benvenuto di Giovanni, Virgin and Child with Saints Jerome and Leonard and Two Angels, fig. 2), and those who prefer to date it in the 1480s. Most scholars in the second group discussed it in relation to the Borghesi altarpiece in San Domenico, Siena (see Benvenuto di Giovanni, Virgin and Child with Saints Jerome and Leonard and Two Angels, fig. 3), when that painting was thought to be a documented work of 1483.4 The Borghesi altarpiece is now widely believed to have been painted at least five years earlier, based on documents implying that it was completed by 1478. Maria Cristina Bandera, the first author to have discussed the Yale painting at any length while aware of this new dating for the Borghesi altarpiece, concured in placing it in the later 1470s, accepting the comparisons adduced by both groups of earlier writers.5 She also highlighted the “modern” composition of the painting, in which a traditional gold ground is replaced with a naturalistic blue sky and the pronounced symmetry of earlier Sienese devotional paintings of similar subject is exchanged for an asymmetrical arrangement of figures, possibly derived from the example of paintings by Francesco di Giorgio. Not the least remarkable feature of this novel composition is the portrayal of the Christ Child in the guise of a young Roman emperor, seated or reclining against a carved marble plinth and supported by angels bedecked in bands of pearls. The Virgin no longer holds and protects her Child but stands behind Him in adoration, her left hand touching her chest in a gesture of humility, her right hand reaching forward with a book and a rosary that the Child reaches to grasp. At the apex of the arched picture field, the Dove of the Holy Spirit hovers in a skillfully foreshortened ellipsis of light, with pulsing vectors of illumination radiating outward from its edges. The mordant gilt lines of grace that flow downward from the Dove to the Virgin and Child are rendered flat along the picture surface, introducing a visual tension between these affectations of modernity and the conventional origins of Benvenuto di Giovanni’s practice, as does the rendering of the gilt cushion on which the Christ Child is notionally seated. The gilded surface of the cushion is delicately tooled to simulate its brocaded texture and the stitching at its edges, and the tassels at its corners are described in painstaking detail, but the cushion is placed well out of contact with any part of the Christ Child’s body, defeating the idea that it might be supporting His weight.

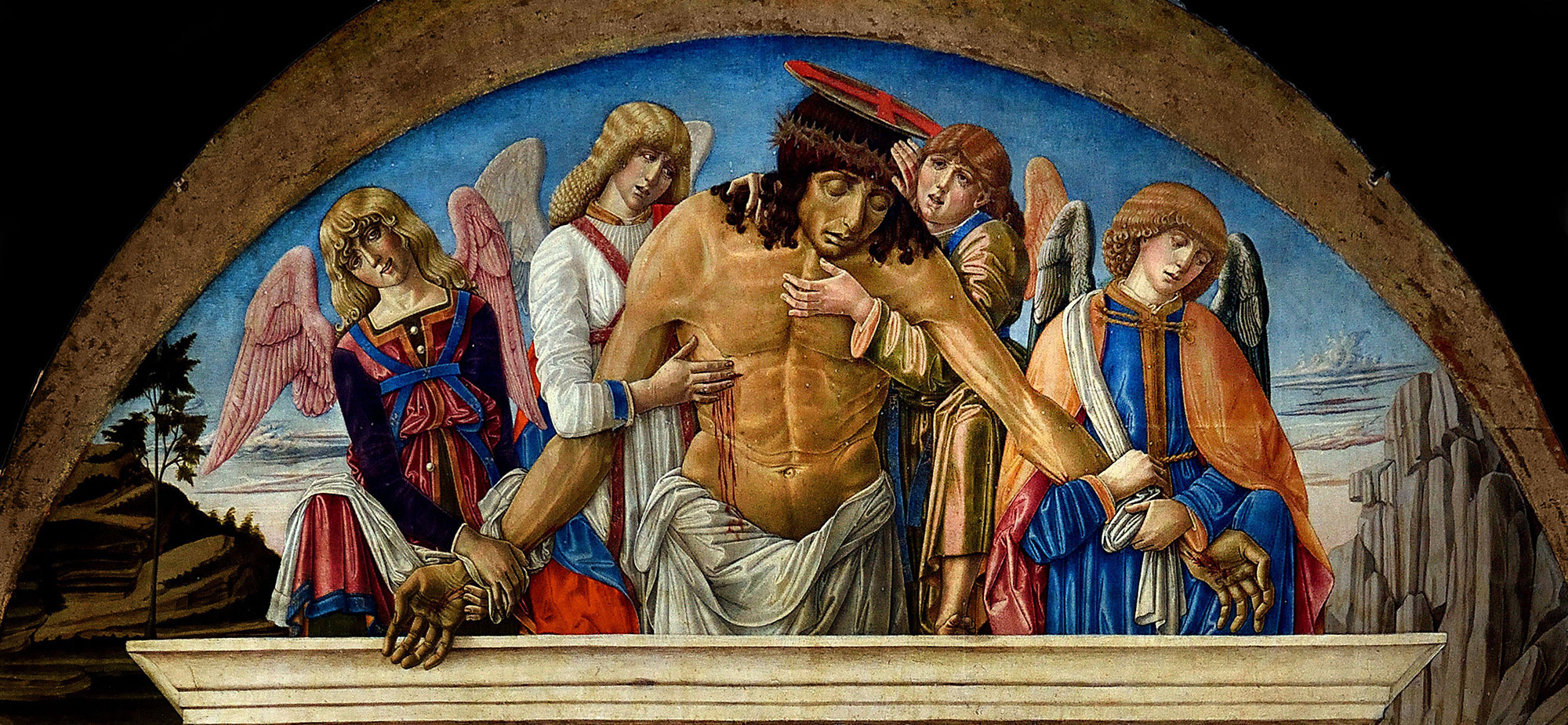

That this “new” direction in Benvenuto’s art does not represent a détente within the development of his career in the 1470s but is rather a definitive departure at a later moment is indicated by a closer consideration of the style of the painting. Meaningful comparisons to the porcelain delicacy and rounded proportions of the figures in either the Montepertuso (1475) or London (1479) altarpieces are absent here, as are similarities to either the Sinalunga Annunciation or the Voterra Nativity, both of 1470.6 The heavier and, at the same time, more elongated proportions of the figures in the Yale painting do find a point of comparison in the Borghesi altarpiece, but only with the angels supporting the figure of the dead Christ in its lunette (fig. 1). It is probable, however, that the lunette—which has been cut to its present shape and size—is not original to this structure and may be a relic of Benvenuto’s altarpiece of 1483 painted for the Bellanti Chapel in San Domenico. The same stiffer, grander proportions appear throughout paintings by Benvenuto plausibly dated to the 1480s, such as the series of frescoes from Sant’Eugenio, Siena, now displayed at the Museo Bardini, Florence (fig. 2), and they culminate in the monumental 1491 altarpiece of the Ascension (fig. 3) from Sant’Eugenio. This is clearly the period in which the Yale painting must be situated, but specifying whether it might have been conceived and executed shortly before, contemporary with, or shortly after the 1491 altarpiece is not possible, given the absence of other firmly dated works from the time.

The unusual silhouette of the panel support of the Yale painting implies an idiosyncratic construction of its original frame, in which most of the outer moldings would have been nailed to it as a backboard, in a manner more commonly encountered among stucco, cartapesta, and terracotta relief sculptures than paintings. Early photographs (fig. 4) show the Yale painting in a tabernacle frame that was removed during the ill-advised cleaning of 1960 and was, apparently, destroyed. There is reason to believe, however, that although repaired and regilt this frame may have been at least in part original. Exposed worm tunnels in the panel support forming a band of damage ranging from 4.0 to 4.5 centimeters wide all around the image indicate the presence there of an engaged molding, glued as well as nailed to the backboard. Such a molding, virtually identical in profile and detail to that seen in photographs of the Yale tabernacle, surrounds the beautifully preserved and only slightly earlier Virgin and Child by Benvenuto di Giovanni in the Robert Lehman Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (fig. 5), although the structure of that frame was altered when it was cut away from the painted panel to permit cradling of the former. Related and substantially intact frames are preserved on a cartapesta Virgin and Child by Francesco di Giorgio formerly in the Lemmers Dansforth collection at Wetzlar, Germany, and now also in the Yale University Art Gallery (see Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Virgin and Child with Angels and Cherubim) and on a terracotta relief of the Virgin and Child by a follower of Francesco di Giorgio in the Pieve di San Leonardo at Montefollonico.7 Alessandro Bagnoli has made a case for attributing these frames to the Sienese woodcarver Ventura di Ser Giuliano di Tura, also known as Tura a Pili (documented 1488–1512).8 While not susceptible of proof, the argument carries a strong degree of plausibility. —LK

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 53, no. 78; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 57, no. 57; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 20, no. 57; Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 143, pl. 8; Berenson, Bernard. The Central Italian Painters of the Renaissance. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1897., 134; Crowe, Joseph Archer, and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle. A History of Painting in Italy, Umbria, Florence, and Siena from the Second to the Sixteenth Century. Vols. 1–4, ed. Robert Langton Douglas. Vols. 5–6, ed. Tancred Borenius. London: J. Murray, 1903–14., 3:118, 5:164; Destrée, Jule. Notes sur les primitifs italiens: Sur quelques peintures de Sienne. Brussels: Éditions Dietrich et Cie/Alinari, 1903. , 79; Perkins, F. Mason. “Pitture senesi negli Stati Uniti.” Rassegna d’arte senese 1, no. 2 (1905): 74–78., 77; Jacobsen, Emil. Das Quattrocento in Siena: Studien in der Gemäldegalerie der Akademie. Strasbourg, France: Heitz, 1908. , 75, pl. 43; Rankin, William. “Cassone Fronts and Salvers in American Collections, VII.” Burlington Magazine 13, no. 66 (September 1908): 377, 380–82. , 381; Berenson, Bernard. The Central Italian Painters of the Renaissance. 2nd rev. ed. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1909., 148; Burroughs, Bryson. “A Sienese Painting.” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 5 (1910): 249–50. , 250; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 163–64, fig. 64; Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 41; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 77; Edgell, George Harold. A History of Sienese Painting. New York: Dial, 1932., 253; Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opere. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 66; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 16. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1937., 400; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Darrell D. Davisson. Benvenuto di Giovanni, Girolamo di Benvenuto: A Summary Catalogue of Their Paintings in America. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1966., 27, 29, 35; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:40, 2: pl. 273; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 186–87, no. 139; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Bandera, Maria Cristina. “Variazioni ai cataloghi berensoniani di Benvenuto di Giovanni.” In Scritti di storia dell’arte in onore di Ugo Procacci, ed. Maria Grazia Ciardi Duprè Dal Poggetto and Paolo Dal Poggetto, 1:311–13. Milan: Electa, 1977. , 1:312; Gunther, Serena. “Benvenuto di Giovanni di Meo del Guasta.” In Allgemeines Künsterlexikon. Munich: K.G. Saur, 1994). , 192; Bandera, Maria Cristina. Benvenuto di Giovanni. Milan: Federico Motta, 1999., 116–17, 119, 142n231, 232, no. 51

Notes

-

Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 143, pl. 8. ↩︎

-

van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 16. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1937., 400. ↩︎

-

Bandera, Maria Cristina. Benvenuto di Giovanni. Milan: Federico Motta, 1999., 89, 224–25, no. 25. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 163–64; Edgell, George Harold. A History of Sienese Painting. New York: Dial, 1932., 253; and Fredericksen, Burton B., and Darrell D. Davisson. Benvenuto di Giovanni, Girolamo di Benvenuto: A Summary Catalogue of Their Paintings in America. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1966., 27, 29, 35. ↩︎

-

Bandera, Maria Cristina. Benvenuto di Giovanni. Milan: Federico Motta, 1999., 232. ↩︎

-

On these two works, see Bandera, Maria Cristina. Benvenuto di Giovanni. Milan: Federico Motta, 1999., 81, 221–22, no. 20; and Bandera, Maria Cristina. Benvenuto di Giovanni. Milan: Federico Motta, 1999., 77, 221, no. 19, respectively. ↩︎

-

Alessandro Bagnoli, in Bellosi, Luciano, ed. Francesco di Giorgio e il Rinascimento a Siena, 1450–1500. Exh. cat. Milan: Electa, 1993. , 410–13; and Laurence Kanter, in Newbery, Timothy J., George Bisacca, and Laurence B. Kanter, eds. Italian Renaissance Frames. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1990. , 40–41. ↩︎

-

Bagnoli, in Bellosi, Luciano, ed. Francesco di Giorgio e il Rinascimento a Siena, 1450–1500. Exh. cat. Milan: Electa, 1993. , 410–13. For Ventura di Ser Giuliano, see also Martini, Laura. “L’oratorio di San Bernardino.” In Domenico Beccafumi e il suo tempo, 600–21. Exh. cat. Milan: Electa, 1990. , 602–4, 621n11. The classicizing frames surviving on altarpieces by Pietro di Francesco Orioli (died 1496) all repeat the profiles, with minor variations in ornament, of the domestic tabernacles discussed above and might have been produced in Ventura di Ser Giuliano’s workshop as well. ↩︎